DNS & BIND 9 DNSSEC Training

1 PDF Version of the training material

2 New terminology used in DNS & BIND

- The terms

masterandslavehave been used to describe primary and secondary authoritative DNS servers in the past.- However this terminology is wrong and misleading, for reasons discussed in the Internet Draft Terminology, Power, and Inclusive Language in Internet-Drafts and RFCs: https://tools.ietf.org/html/draft-knodel-terminology

- In this document, and in configuration examples, we are using the

new terms

primary(instead ofmaster) andsecondary(instead ofslave) whenever possible. - BIND 9 has started adopting the new terms with BIND 9.14, however

the transition is not complete, and some terms in configuration

statements still use the old terms. This will change with

future releases

- If you use an older version of BIND 9, please substitute the new terms for the older ones

- The old terminology will also be found in older books and standards documents (RFCs and Internet Drafts)

- DNS terminology can be confusing and is sometimes overloaded. RFC 9499 DNS terminology ( https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc9499 ) attempts to collect and document the current usage of DNS terminology.

3 DNS 1x1

3.1 DNS - The Domain Name System

DNS is like chess

the rules are simple

but the chances to loose the game

are endless

3.2 DNS - The Domain Name System

- First developments 1981-1983

- Introduced into the Internet between 1983 and 1988

- Replacement for the static

hosts.txtfile - Continuously updated and expanded

- Scales with the growth of the Internet

- Minimal built-in security

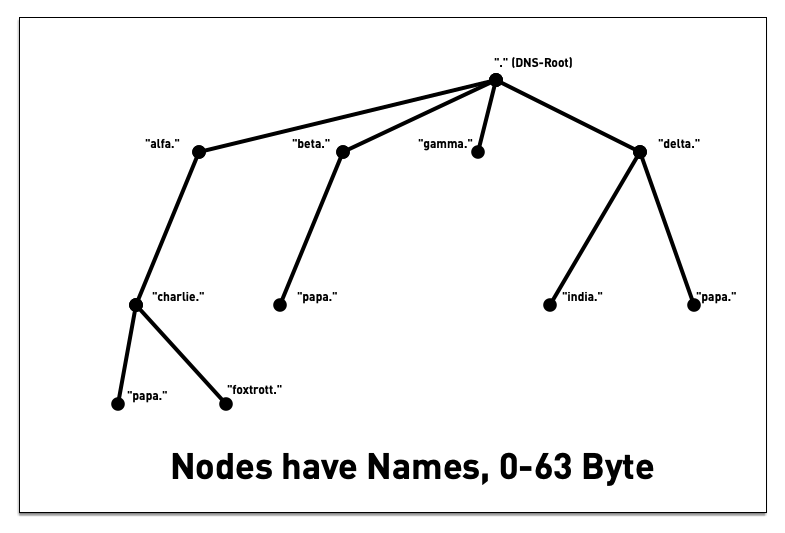

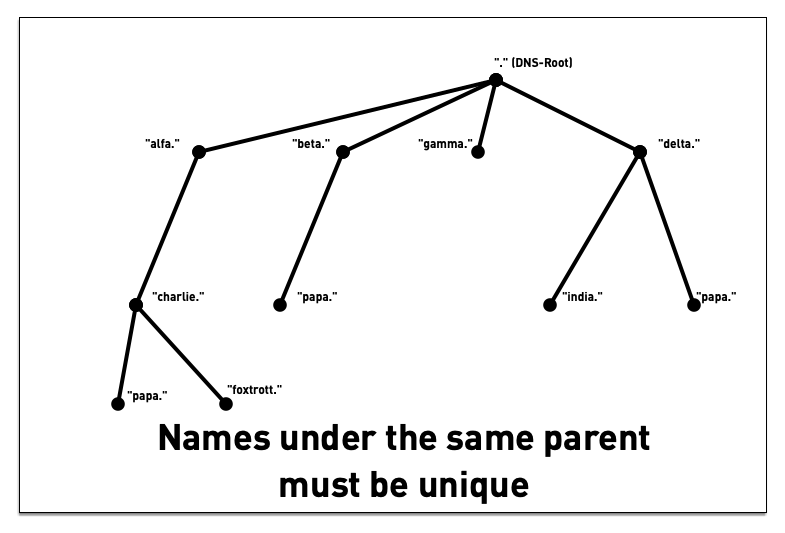

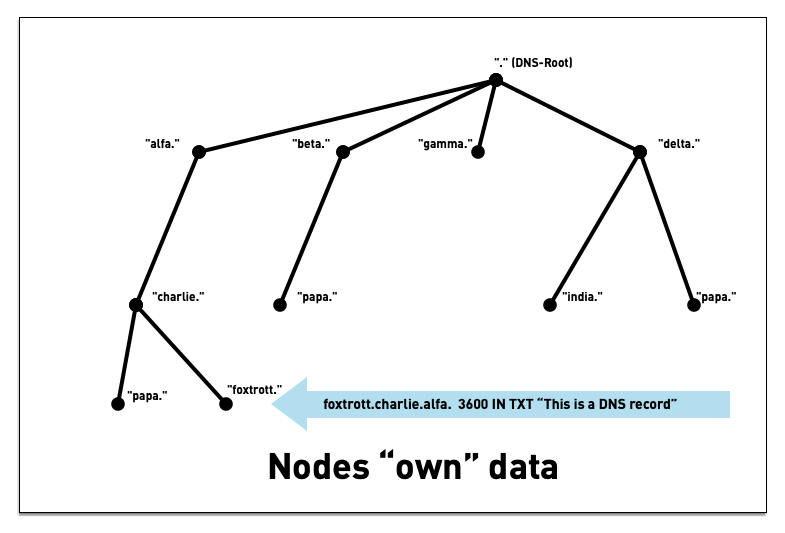

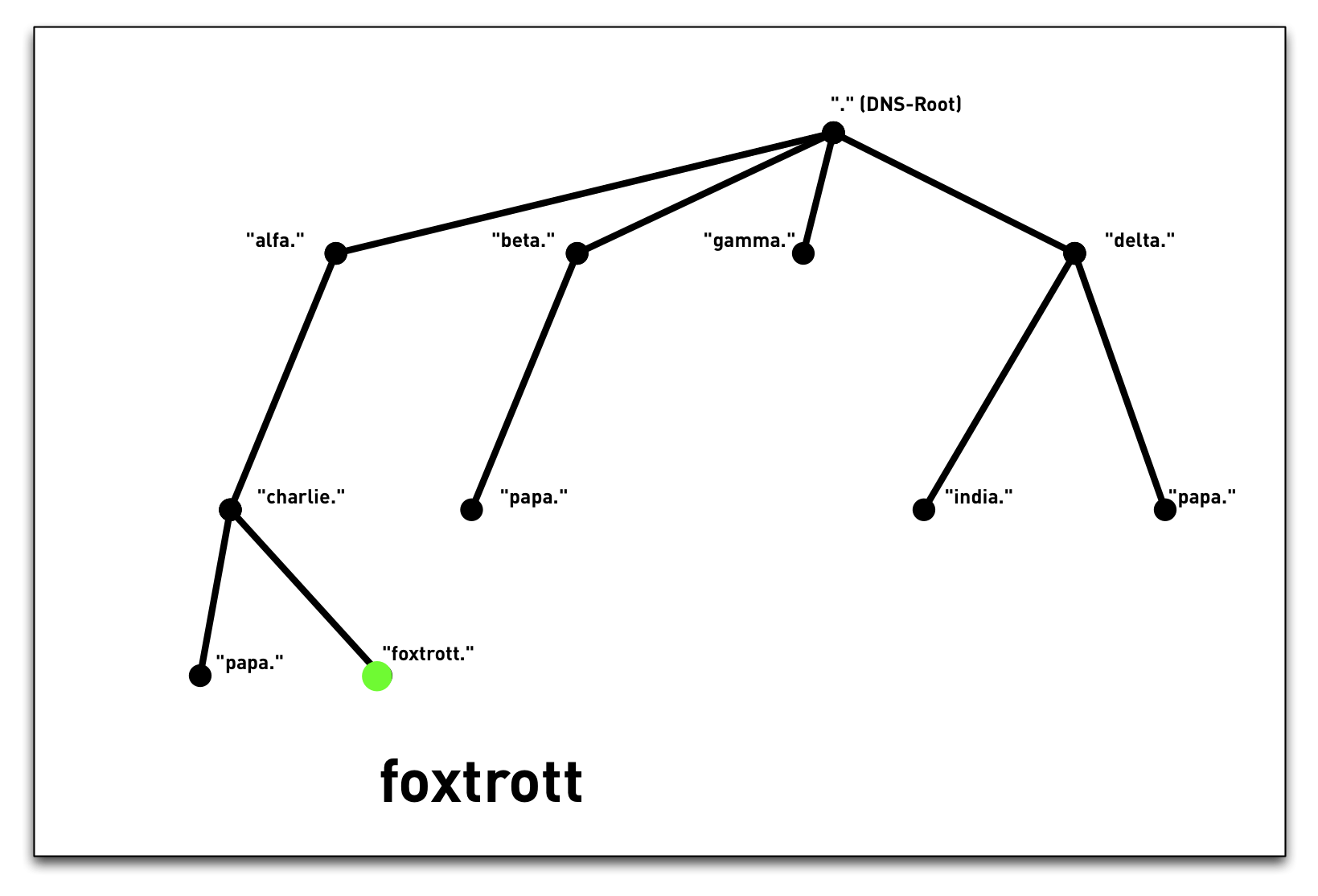

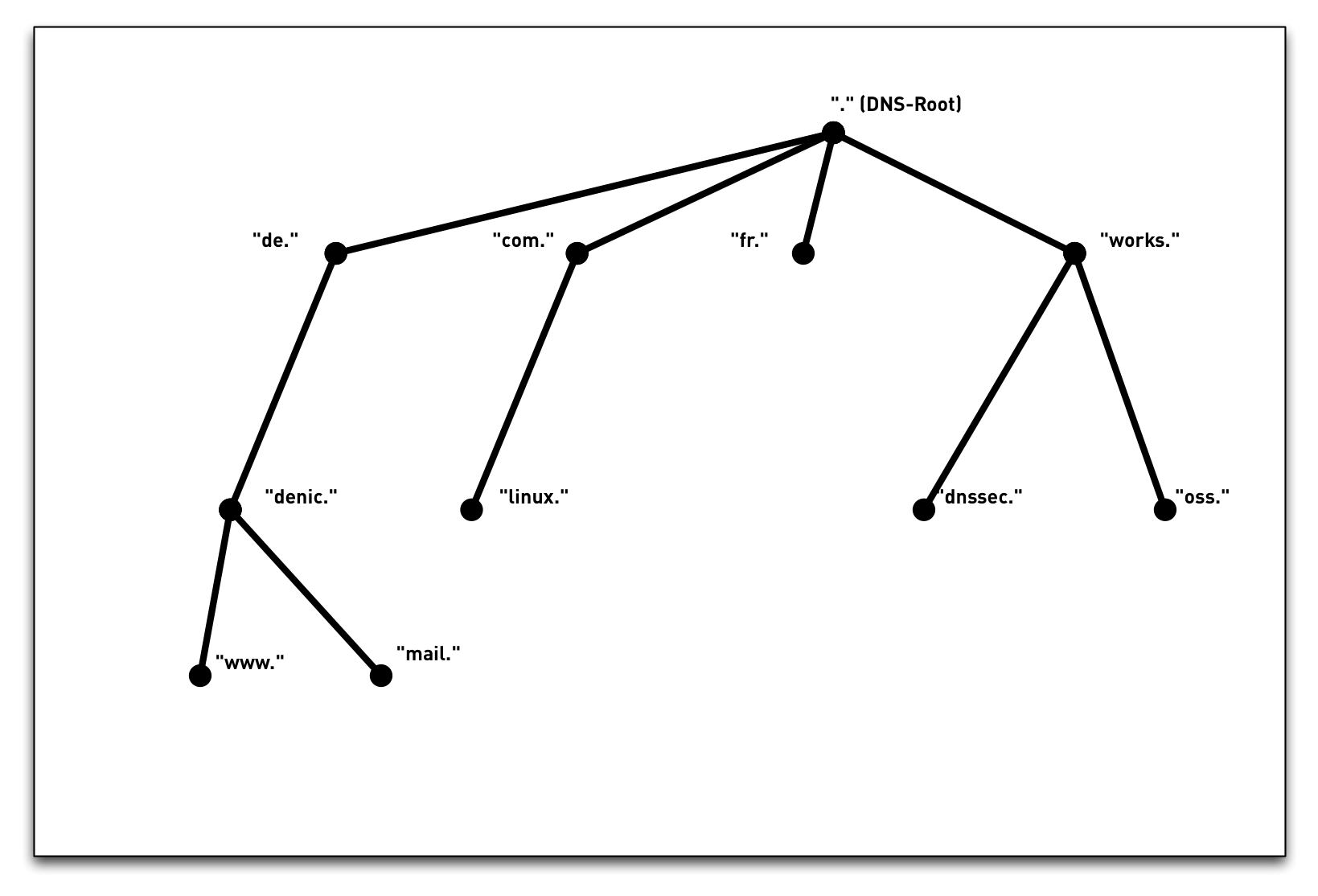

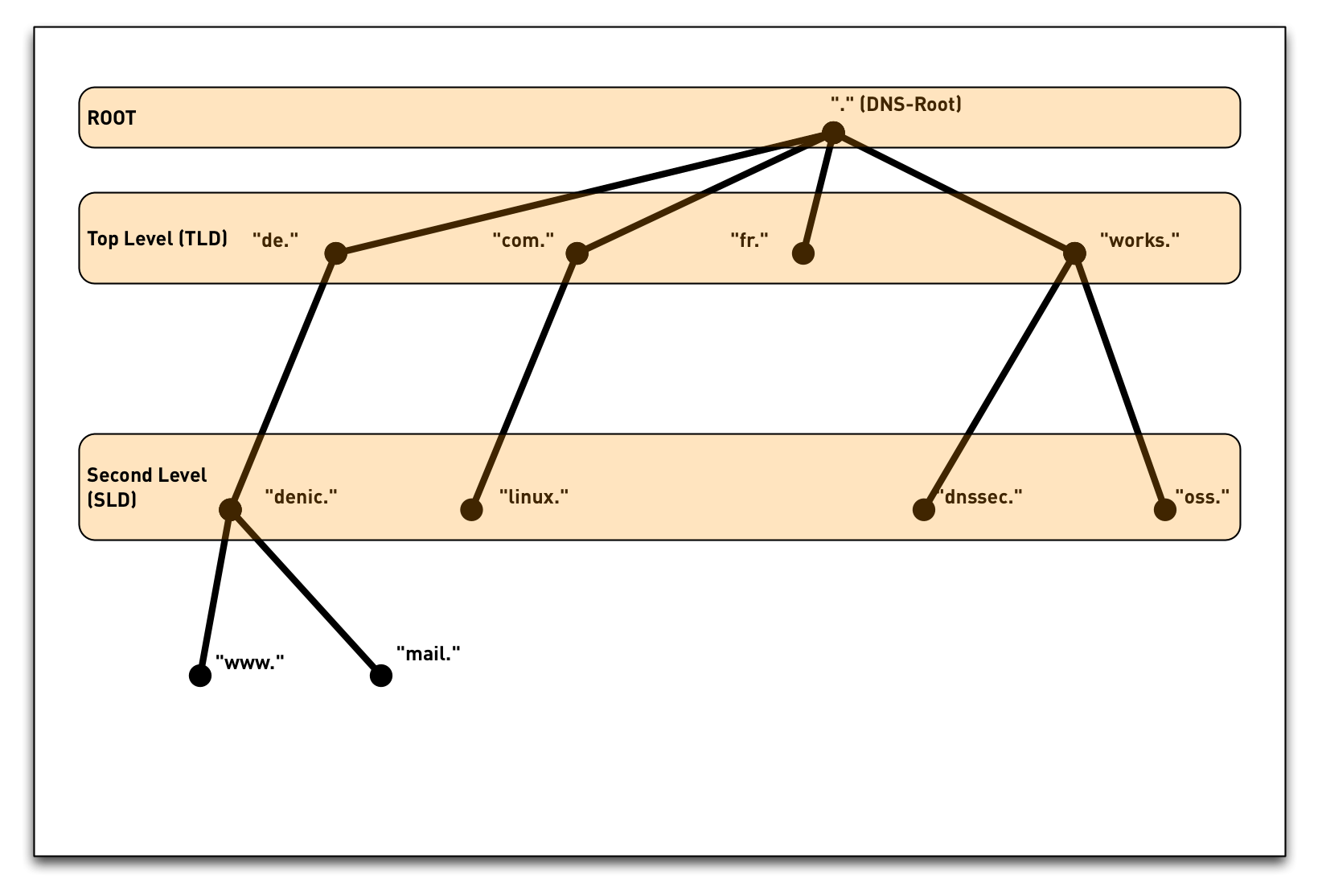

3.3 DNS namespace

3.4 DNS namespace

3.5 DNS namespace - "Label"

3.6 DNS namespace - "Label"

3.7 DNS namespace - "Label"

3.8 DNS namespace

3.9 Internet namespace

3.10 Internet namespace

3.11 RFC 9476 - The .alt Special-Use Top-Level Domain

- The

.altTLD has been created for all applications that want to use a DNS style name resolution, but don't use the DNS protocol - Applications that use DNS style names without the DNS protocol

should use names under the

.altTLD to not collide with DNS names - RFC 9476: https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc9476.html

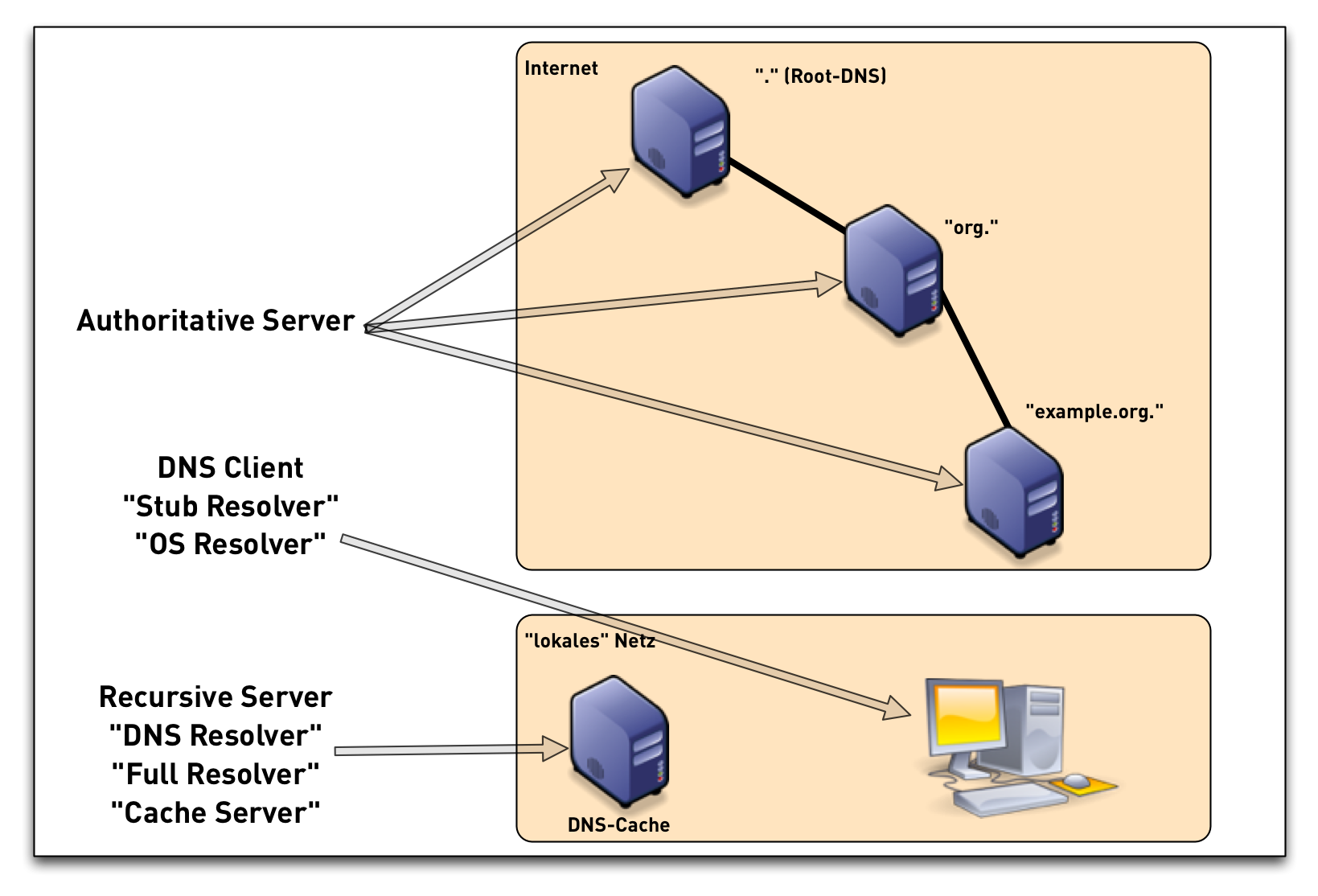

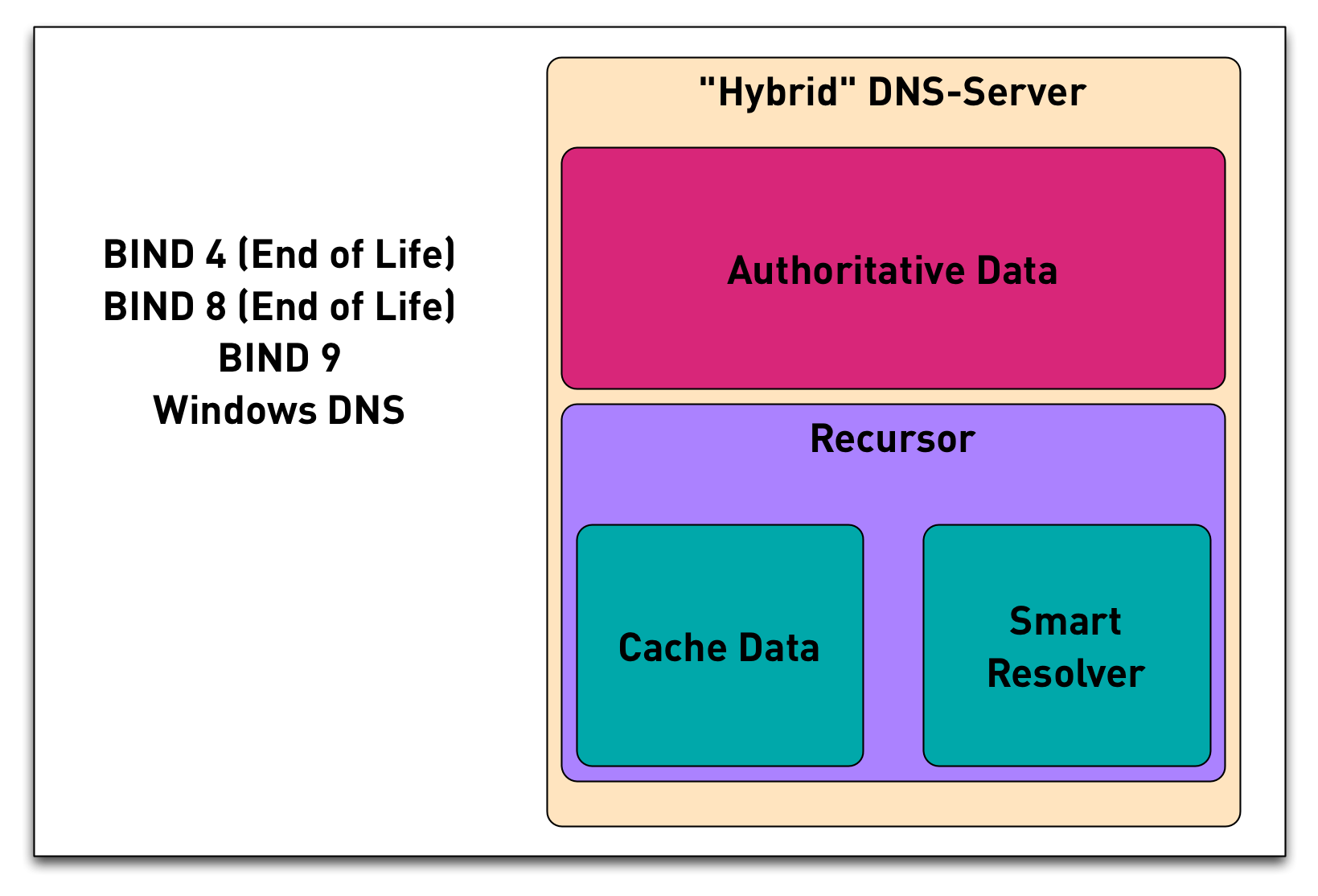

3.12 DNS components

3.13 DNS components - Hybrid-DNS

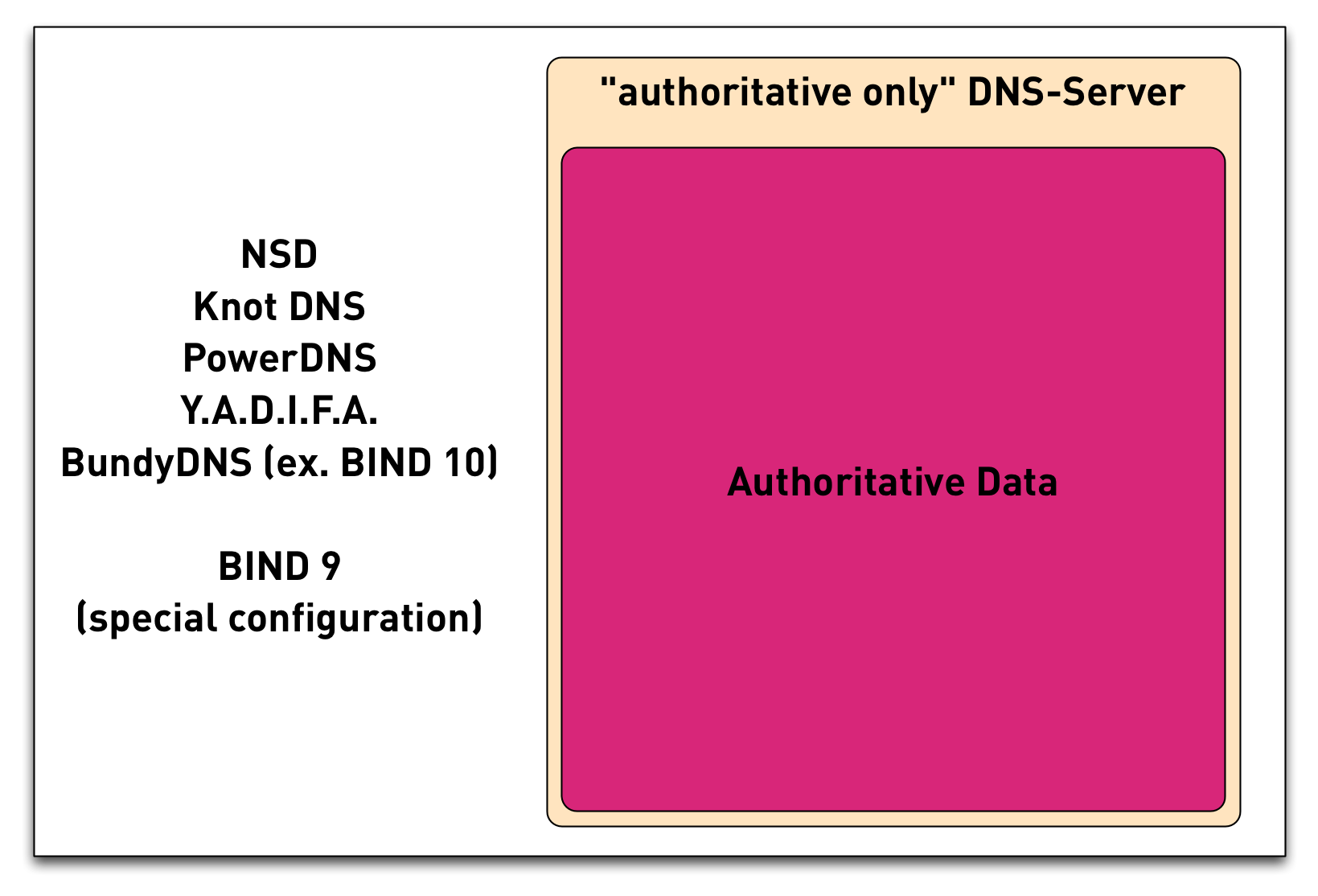

3.14 DNS components - Authoritative Only

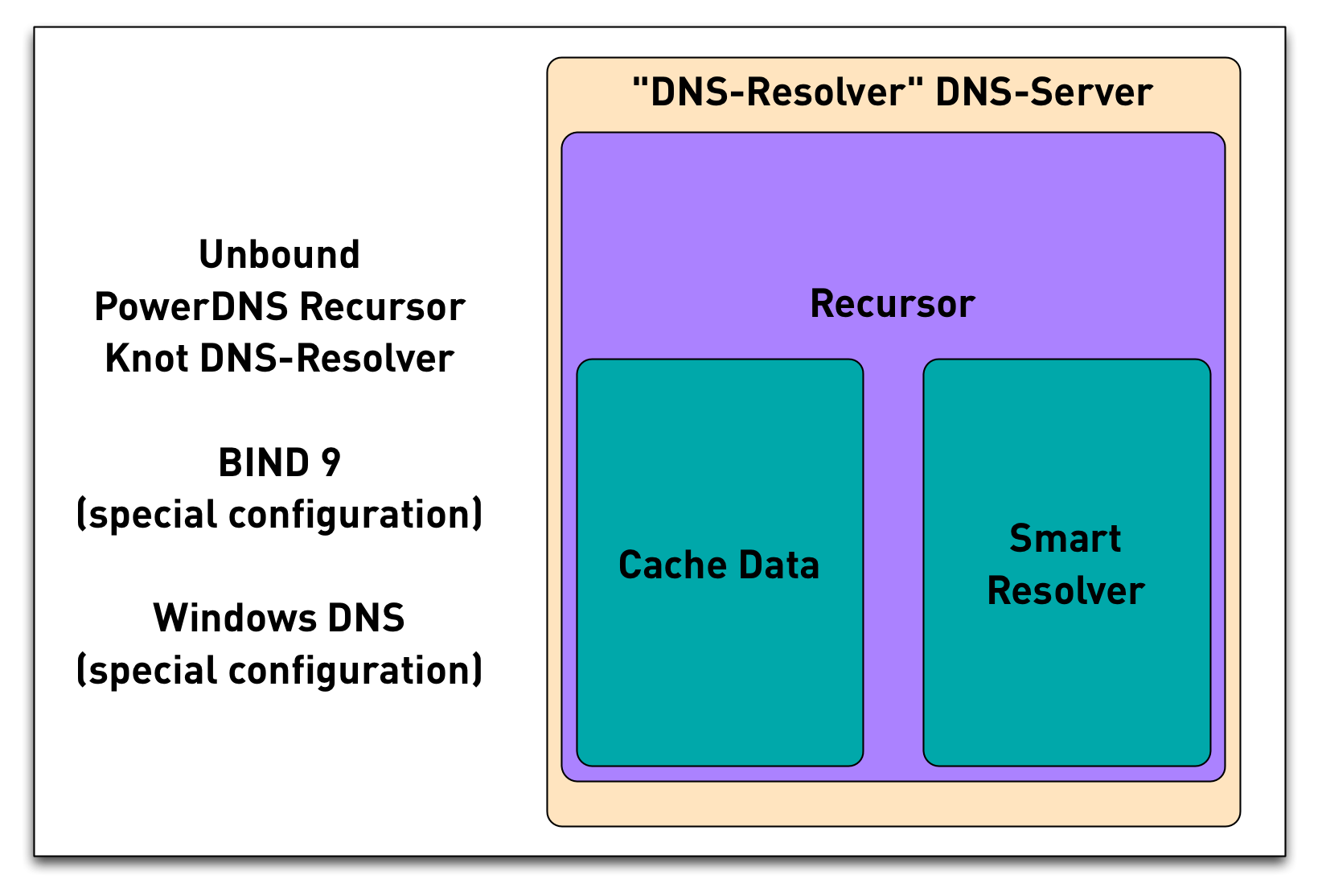

3.15 DNS components - DNS Resolver

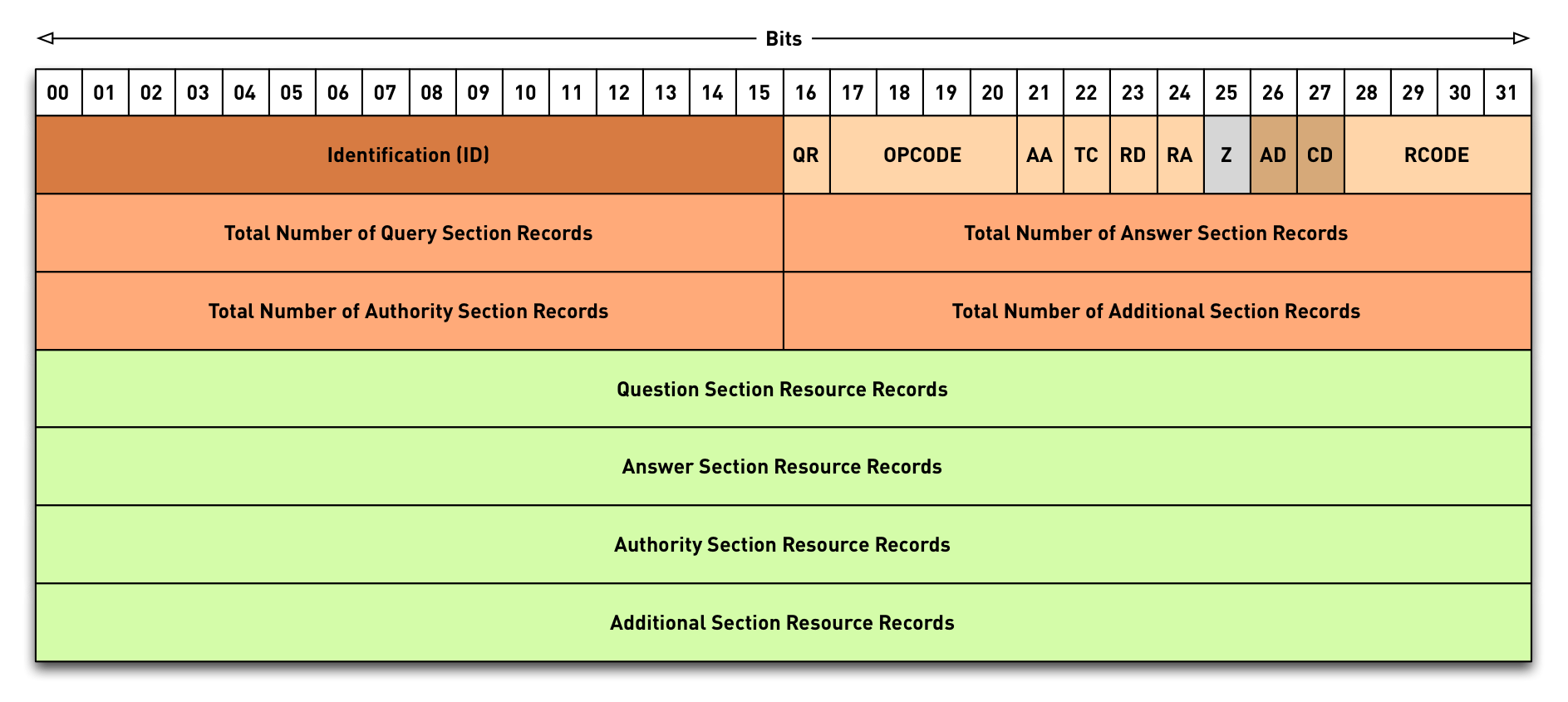

3.16 DNS message format

3.17 DNS Resource Records

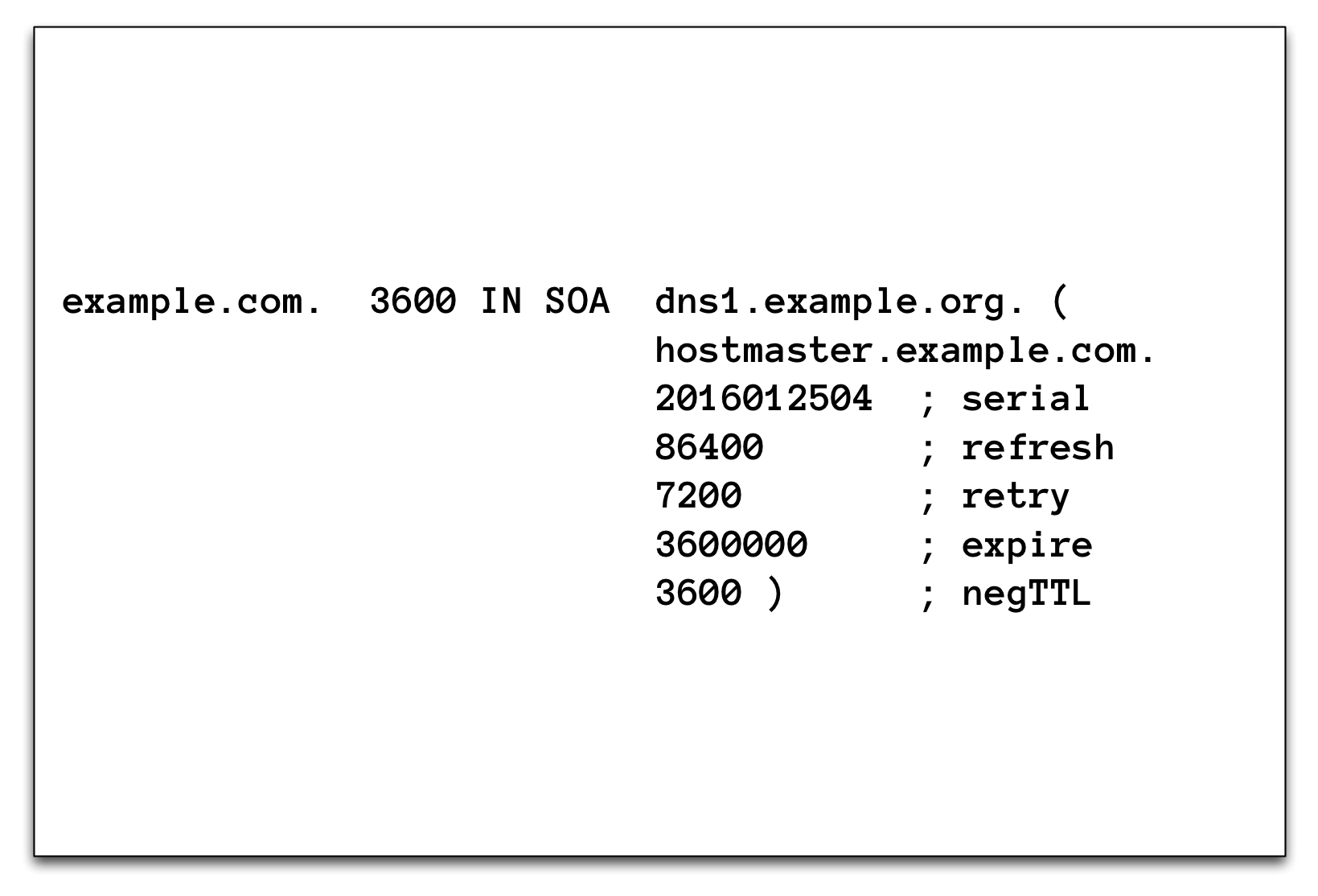

3.17.1 SOA Record

3.17.2 Negative Caching

- The last value of the SOA record (together with the TTL-value of the SOA record, the lowest value will be used) controls how long negative DNS responses are stored in a DNS cache

- Negative responses are NXDOMAIN and NXRRSET/NODATA

- Error-Responses (FORMERR, REFUSED …) will not be cached

- SERVFAIL is cached for

servfail-ttlseconds (default 1, maximum is capped to 30) - RFC 9520 - Negative Caching of DNS Resolution Failures (December 2023) mandates that DNS resolution failures MUST be cached between 1 second (min) and 5 minutes (max)

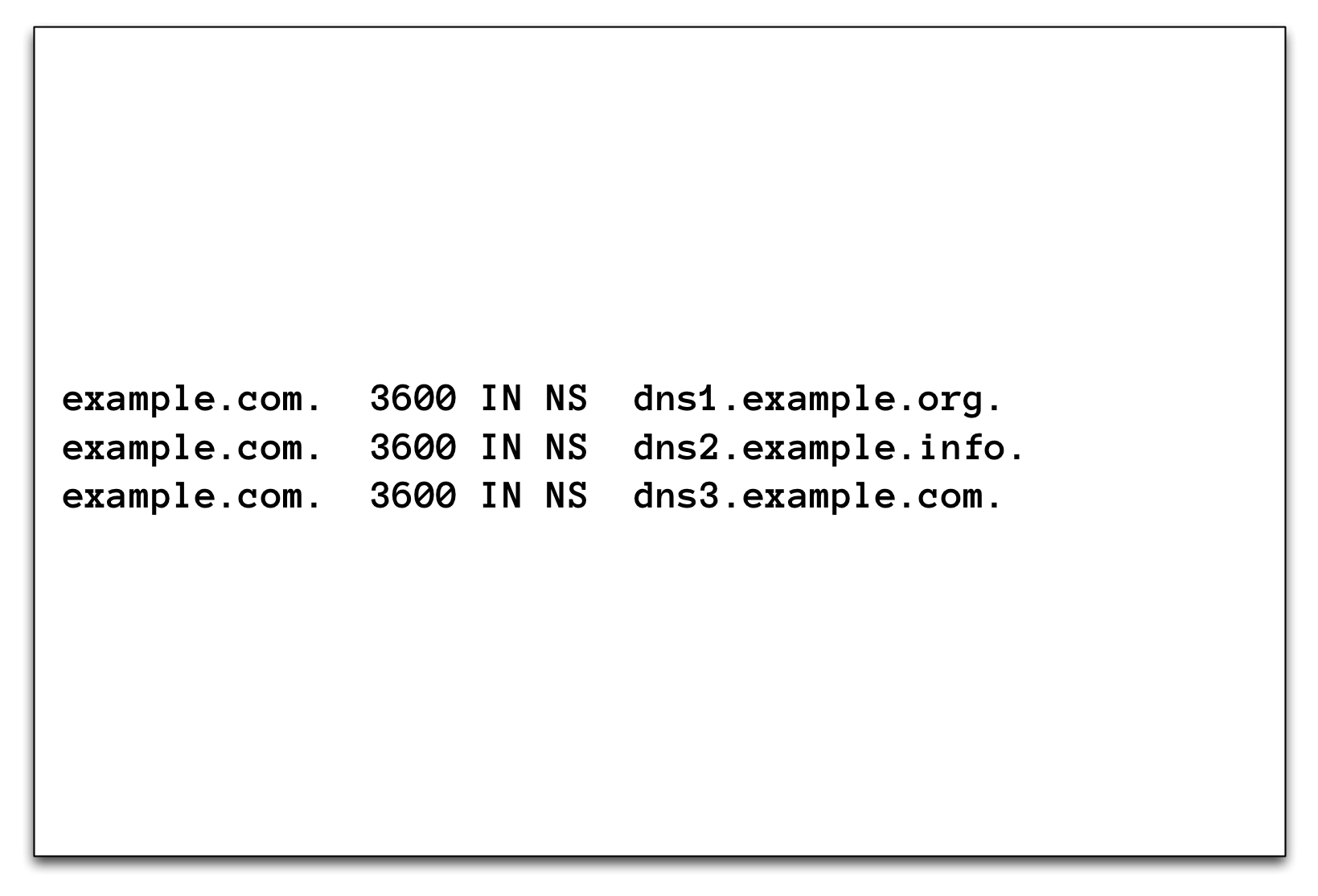

3.17.3 NS record

3.17.4 NS record

- NS records create the DNS delegation

- The NS record in the parent zone (delegation) SHOULD always match the NS records in the (delegated) zone (see When parents and children disagree)

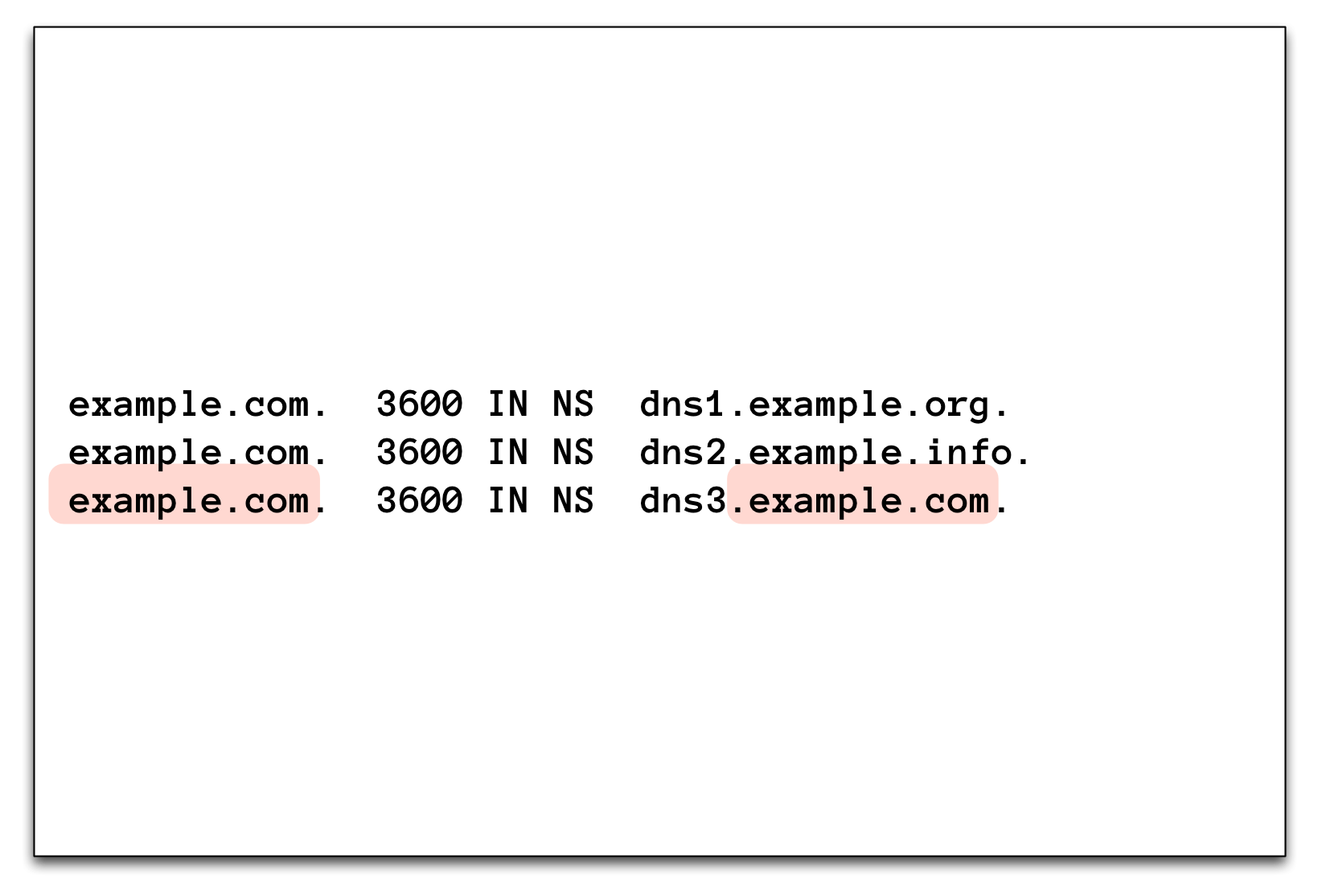

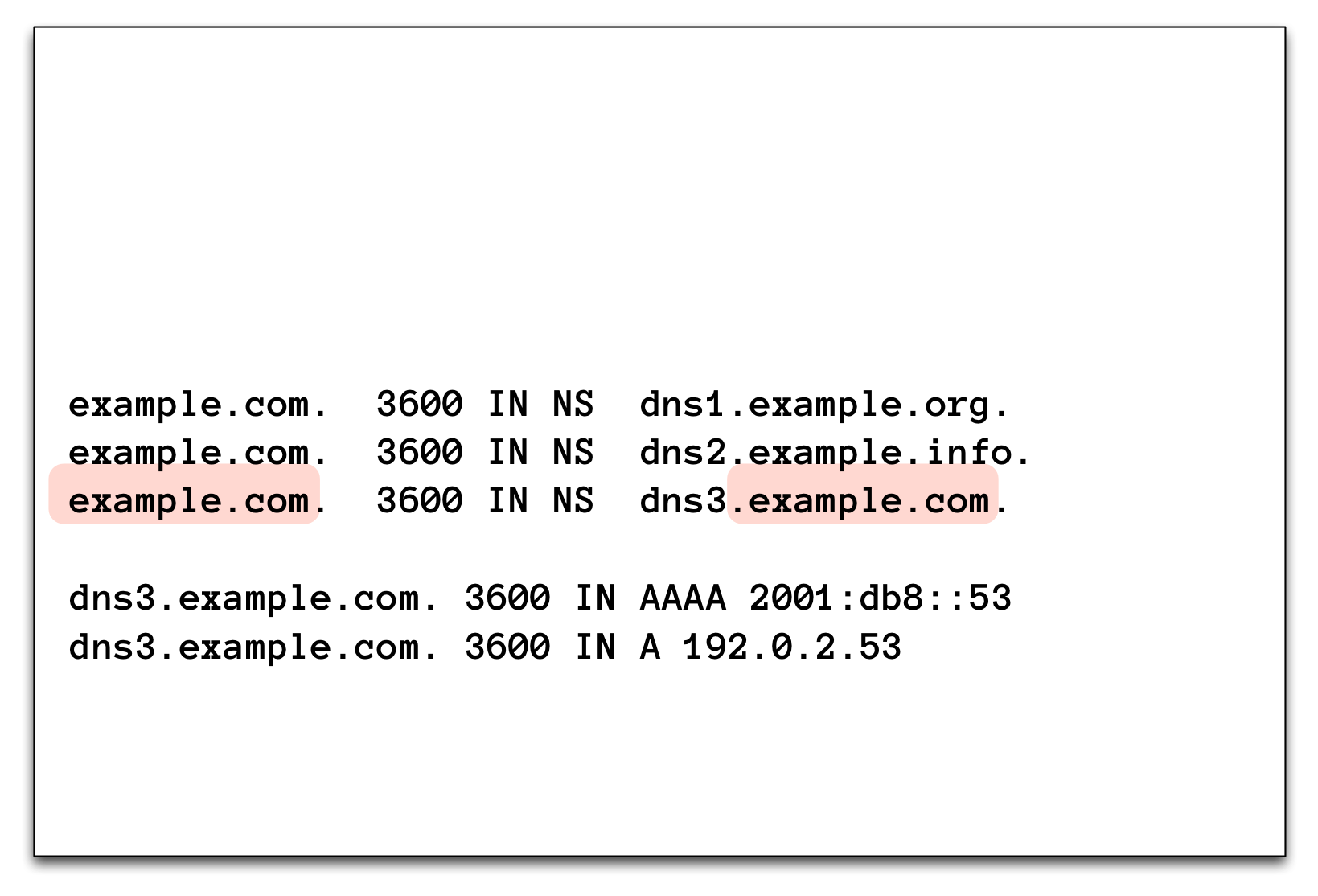

- For domain names of authoritative DNS servers inside the delegated domain, the parent zone must be augmented with Glue records (A/AAAA records of the authoritative DNS Servers) to make the delegation work.

- See RFC 9471 - DNS Glue Requirements in Referral Responses (September 2023) for details.

3.17.5 Glue (1)

3.17.6 Glue (2)

4 An Intro to DNSSEC

4.1 DNS Security (or lack of)

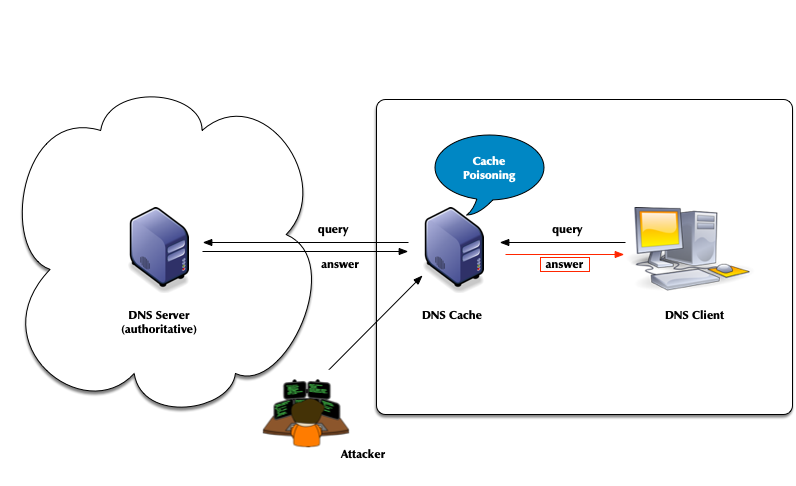

- The classic DNS from 1983 has not been designed with security in mind

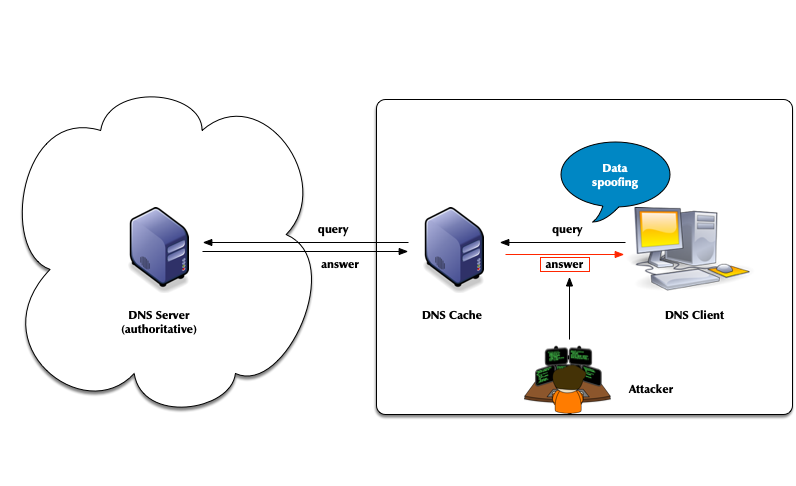

- Attack vector: DNS cache poisoning

- Attack vector: Men-in-the-Middle data spoofing

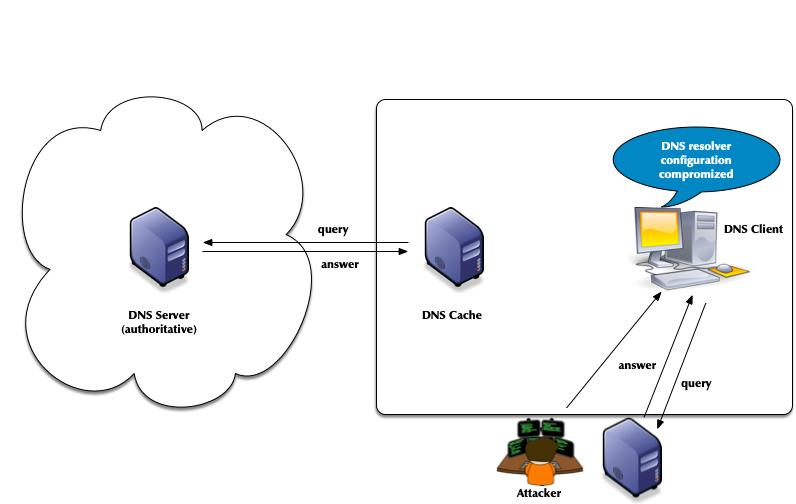

- Attack vector: changes to the client DNS resolver configuration

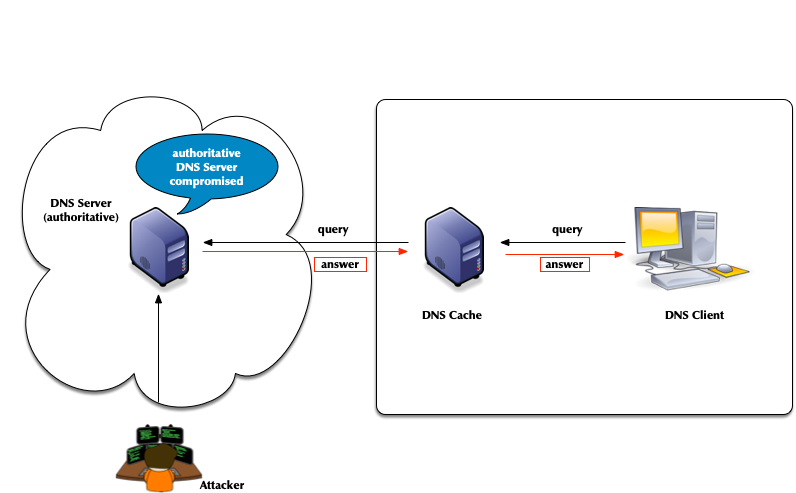

- Attacks of authoritative DNS servers

- DNSSEC can help

5 Cryptography in DNS (short)

5.1 Cryptography for DNS Admins

- Cryptography has four purposes:

- Confidentiality – keeping data secret

- Integrity – Is it "as sent"?

- Authentication – Did it come from the right place?

- Non-Repudiation – Don’t tell me you didn't say that.

- DNSSEC implements: Authentication & Integrity

- The IETF has added confidentiality since 2016:

- DNS uses different authenticity and integrity techniques depending on the application.

- Symmetric Cryptography

- Message Digests (aka: hashes, hash values, fingerprints)

- Message Authentication Codes

- Asymmetric Cryptography

- Digital Signatures

5.2 Symmetric Cryptography

- Symmetric cryptography provides both integrity and authenticity.

- A single key is stored and used by both (all) parties.

- The key encrypts and decrypts.

- The key is a shared secret.

- The system is known as pre-shared key (PSK).

- Securely getting the key to all parties can be a challenge.

- Symmetric cryptography requires mutual trust.

- "My security is good, but what about the other person's?"

- If all sides are administered by one party, trust is a non-issue.

- For DNS, Pre-Shared-Keys (PSK) work well:

- between primary and secondary servers (TSIG).

- for dynamic DNS updates (TSIG).

- for controlling BIND 9 with

rndc(TSIG).

- For DNS, PSKs do not work well:

- between DNS Resolver servers and authoritative DNS servers (DNSSEC).

- between stub resolver & DNS Resolver servers (DNSSEC amongst other).

5.2.1 Confidentiality: Not the Goal

- A Pre-Shared Key (PSK) could be used to encrypt a message.

- If it decrypts, confidentially, integrity, and authenticity are assured.

- However, confidentiality was not a design goal (of DNSSEC).

- Encrypting everything is computationally expensive.

- The alternative is more complicated but less expensive.

5.2.2 Message Digest

- Creating a hash of the message is a light-weight alternative to

encrypting everything.

- A hash is also known as a hash value, a message digest (MD) or a fingerprint.

- The sender runs a cryptographic hashing algorithm on the message to

produce a fixed-length hash.

- The message and hash are sent over an insecure path.

- As the sender did, the receiver hashes the message.

- If the hashes match, the message was not modified. Message integrity is proven.

- However, the receiver does not know if the message and hash were both replaced: Message authenticity is unknown.

- Confidentiality is not provided.

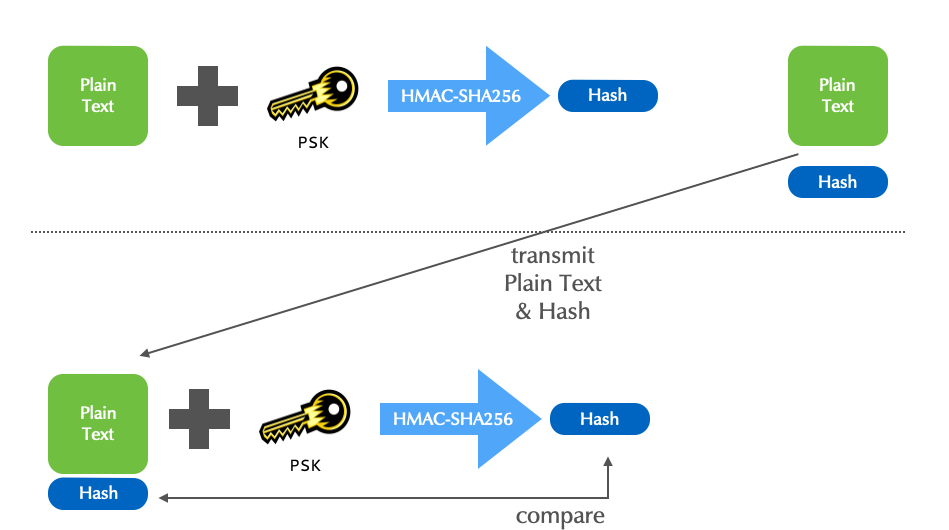

5.2.3 Message Authentication Codes

- Hashing, with a symmetric key added to the input, efficiently

provides integrity and authenticity.

- There is no confidentiality.

- A MAC is a fingerprint (MD, hash) created with the message and a PSK as input.

- The MAC described here, is a keyed HMAC (Hash-based message

authentication code).

- It is used by DNS.

- Although HMACs efficiently assure both the sender's authenticity,

and the message's integrity, not all applications can use

(pre)shared keys.

- "Am I really seeing the website

mybank.example?" - "Is the email I'm reading really from Edward Snowden?"

- "Is this RRSet actually for

theguardian.com?"

- "Am I really seeing the website

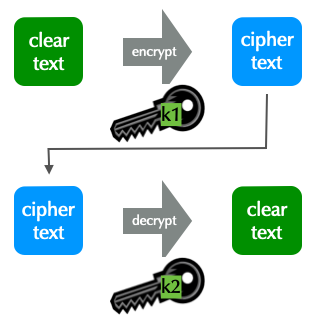

5.3 Asymmetric Cryptography

- In DNS, asymmetric cryptography is used for DNSSEC.

- This asymmetric cryptography section is a short overview.

- Asymmetric cryptography uses two keys, a pair.

- Data encrypted with one key can only be decrypted by the other.

- A key cannot decrypt what it encrypted!

- One key of a pair is declared as public, the other as private.

- The private key is highly sensitive, never shared, and must be well protected.

- The public key is made widely available without concern for who knows it.

- The technique is known as public key encryption.

5.3.1 Two Applications for public key (PK) Encryption

- PK encryption is used for privacy, to assure only the intended

receiver can read a message.

- Data integrity is also assured.

- Used in DNS-over-TLS and DNS-over-HTTPS

- PK encryption is used for authenticity, assuring the recipient,

that the message came from a specific sender.

- This is known as signing a message.

- Data integrity is also assured.

- Used in DNSSEC, as well in DNS-over-TLS and DNS-over-HTTPS

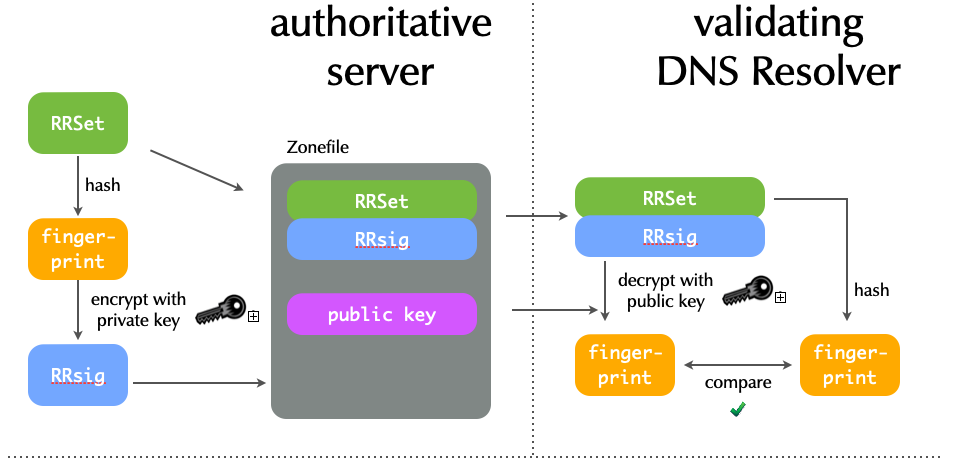

5.3.2 PK Application 2: Encryption for Authenticity

- To assure authenticity, a sender encrypts a message with her

private key.

- Anyone decrypting the message with the public key is assured it came from the holder of the private key.

- The message is encrypted, but there is no privacy.

5.3.3 PK Application 2: Encryption for Authenticity: Digital Signatures

- For efficiency, the message itself is not encrypted.

- The message is first hashed to create a fingerprint.

- The fingerprint is encrypted.

- The signed fingerprint is a digital signature (aka encrypted fingerprint and encrypted hash).

5.3.4 Digital Signatures in DNSSEC

5.4 DNSSEC

- The DNS Security Extensions, described in RFC 2065 (old DNSSEC), allow a zone administrator to digitally sign zone data

- The base DNSSEC RFCs:

- RFC 4033 to 4035 - Updates DNSSEC to DNSSECbis, published March 2005:

- RFC 4033 - DNS Security Introduction and Requirements

- RFC 4034 - Resource Records for the DNS Security Extensions

- RFC 4035 - Protocol Modifications for the DNS Security Extensions

- The DNS security extension DNSSEC secures DNS data by augmenting

the data with cryptographic signatures

- The owner (administrator) creates a pair of private and secret keys for each DNS zone (asymmetric crypto)

- The owner/administrator signs all DNS data with the private/secret key

- The recipient of the data (DNS resolver or client operating

system or application) will verify (validate) the data

- That the data has not been changed on the server nor during transit

- That the data comes from the owner (the owner of the private key)

- DNSSEC signs data to guarantee authenticity and integrity.

- It assures a client that a RRSet is from the proper authoritative sever and has not changed.

- DNSSEC does not encrypt data to provide privacy.

- Anyone can find out the RRSets you request.

- DNS Servers that support DNSSEC

- BIND 9: Authoritative server and validating resolver

- NSD from NLnet Labs: Fast authoritative server

- Unbound from NLnet Labs :Fast and secure validating resolver

- Windows DNS Server: Authoritative server and validating resolver

- PowerDNS authoritative: Authoritative DNS Server with (optional) SQL Database backend

- PowerDNS Recursor: a resolver with support for DNSSEC validation

- Knot-DNS: fast authoritative DNS Server from

nic.cz - Knot-DNS Resolver: recursive server with DNSSEC from

nic.cz

5.5 TSIG vs. DNSSEC

- TSIG uses a keyed cryptographic hash algorithm, which requires that both endpoints share a key

- DNSSEC uses public key cryptography, which doesn't require shared keys

- Zone data is signed by the zone administrator

- This provides an end-to-end integrity check between producer (DNS Administrator) and consumer (Resolver, Application)

5.6 DNSSEC:Design Choices Made

- DNSSEC signs RRSets, but alternatives were available to the designers:

- An entire DNS message could be signed.

- Just the answer section of a message could be signed.

- Each RR in an answer could be signed.

- DNS messages and answer sections are dynamically generated when a query arrives. = The signatures would have to be dynamically generated.

- RRs and RRSets aren't modified when a query arrives at an

authoritative server.

- Signatures can be created when the zone is compiled.

- Signing each RRSet is most effectively and what is done.

6 DNSSEC in a nutshell

- In DNSSEC, each zone has one or more key pairs.

- The private key of each pair

- Is stored securely (probably on a hidden primary)

- Is used to sign zone data

- Should never be stored in a RR

- The public key of each pair

- Is stored in the zone data, as a DNSKEY record

- Is used to verify zone data

- The private key of each pair

- A private key signs the hashes of each RRSet in a zone.

- The public key is accessible through a standard RR.

- Recursive servers or clients query for the public key RR in order to decrypt a hash.

- The RR is known as the DNSKEY and covered below.

6.1 DNSSEC records

6.1.1 RRSIG

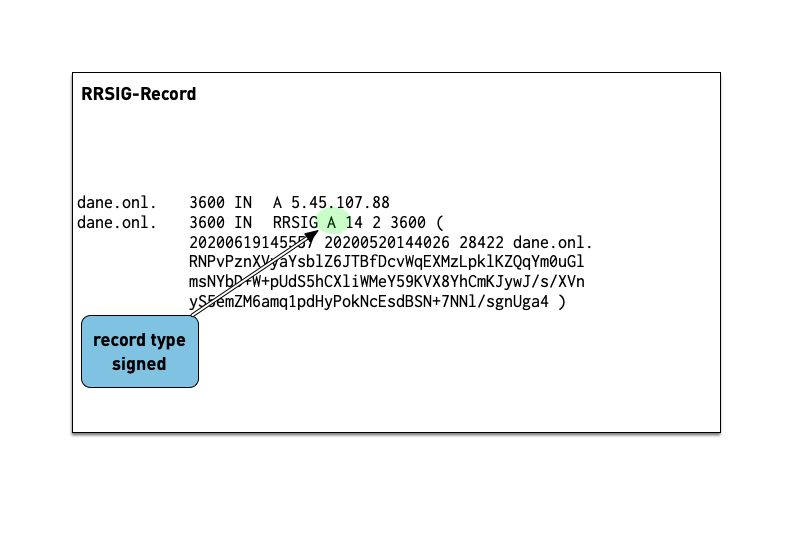

- The RRSIG records holds the cryptographic signature over the DNS data. The first field of the RRSIG holds the type this RRSIG is for. Together with the domain name of the RRSIG this data is important to match the signature to the data record.

- A zone's private key signs the RRSets in the zone.

- The signatures are added to the zone as RRSIG RRs.

- If two key pairs are in use, each RRSet is signed twice, and there is double the number of signatures.

- Signatures have start and expiration times (typically a month or

less apart).

- They must be replaced before expiring. BIND 9 can automate the signature updates.

- Keys don't have expiration timers.

- Work on the DNS resolver machine

- Ask for the DNSSEC signature of

dnssec.works NS:$ dig dnssec.works NS +dnssec +multi

- Answer these questions

- Which algorithm is this zone using? check the number against IANA Domain Name System Security (DNSSEC) Algorithm Numbers

- When does the signature expire?

- When did the signature become valid?

6.1.2 DNSKEY

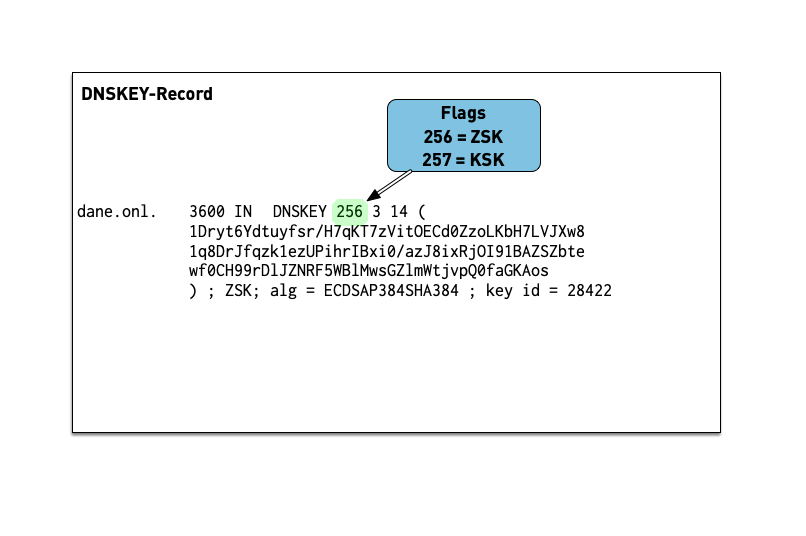

- The public key of a DNSSEC key pair is stored in an DNSKEY RR.

- The private key is not publicly available or accessible through DNS.

- DNSKEY RRs are stored in the zone they can verify.

- This conveniently means the zone administrator can sign all the RRSets and create the DNSKEY RRSet.

- Work on the DNS resolver machine

- Ask for the DNSSEC keys of

dnsworkshop.cz:$ dig dnsworkshop.cz DNSKEY +dnssec +multi

- Answer these questions

- Which algorithm is this zone using?

- Compare the size of keys and signature with the zone

dnssec.works - The sizes of both DNS answer messages as reported by

dig

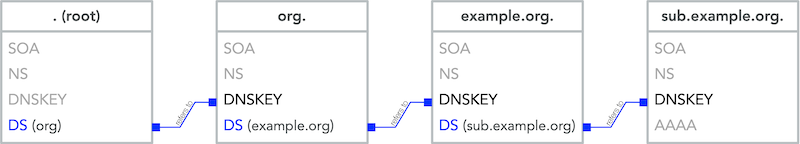

6.2 The chain of trust in DNS

- If an attacker breaks into the server with the master zone file, she can change any data, including the DNSKEY RRSet.

- The DNSKEY RRSet is signed by the zone's private key!

- That signature, even when validated, proves nothing.

- It's a circular problem.

- External validation is needed, but we can't look beyond DNS.

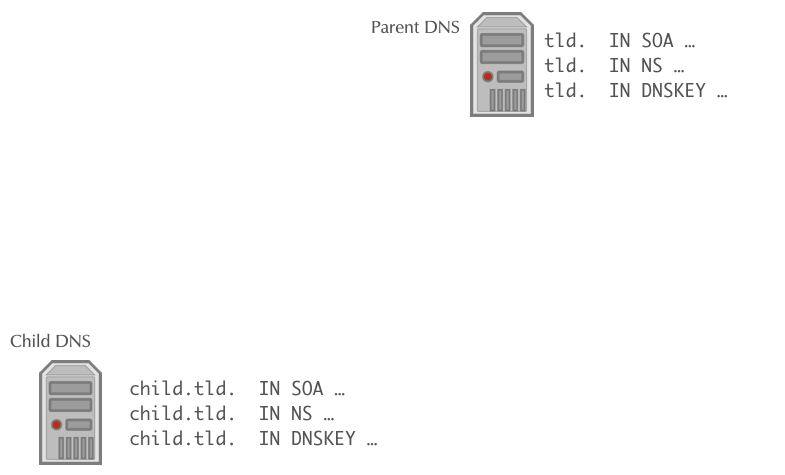

- DNSSEC creates a chain of trust between the parent zone and the child zone

- Applications and DNS resolver can follow the chain of trust to a configured trust anchor to validate the DNS data

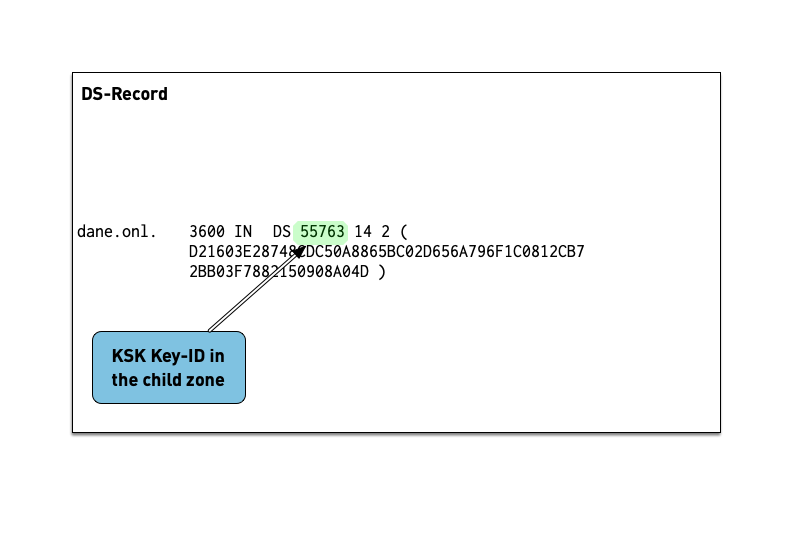

6.2.1 DS Record

- The Delegation Signer (DS) records holds the hash of the

Key-Signing-Key of a DNSSEC signed child zone.

- It is used to verify that the KSK has not been replaced without permission

- The DS record is usually submitted to the parent zone operator

via a web-based or API system implemented by the domain reseller

(registrar)

- This interface can become a target for attacker that want to change data in a DNSSEC signed zone and should be protected (two factor signon, registry lock etc).

- Work on the DNS resolver machine

- Ask for the DNSSEC delegation signer of

isc.org:$ dig isc.org DS +dnssec +multi

- Answer these questions into the chat

- Which DNSSEC-Key-Algorithm is this zone using?

- What is the current key-id of the KSK in the zone

isc.org? - What hashing algorithm is used for the DS record of

isc.orgcheck against Delegation Signer (DS) Resource Record (RR) Type Digest Algorithms?

7 DNSSEC signing and validation

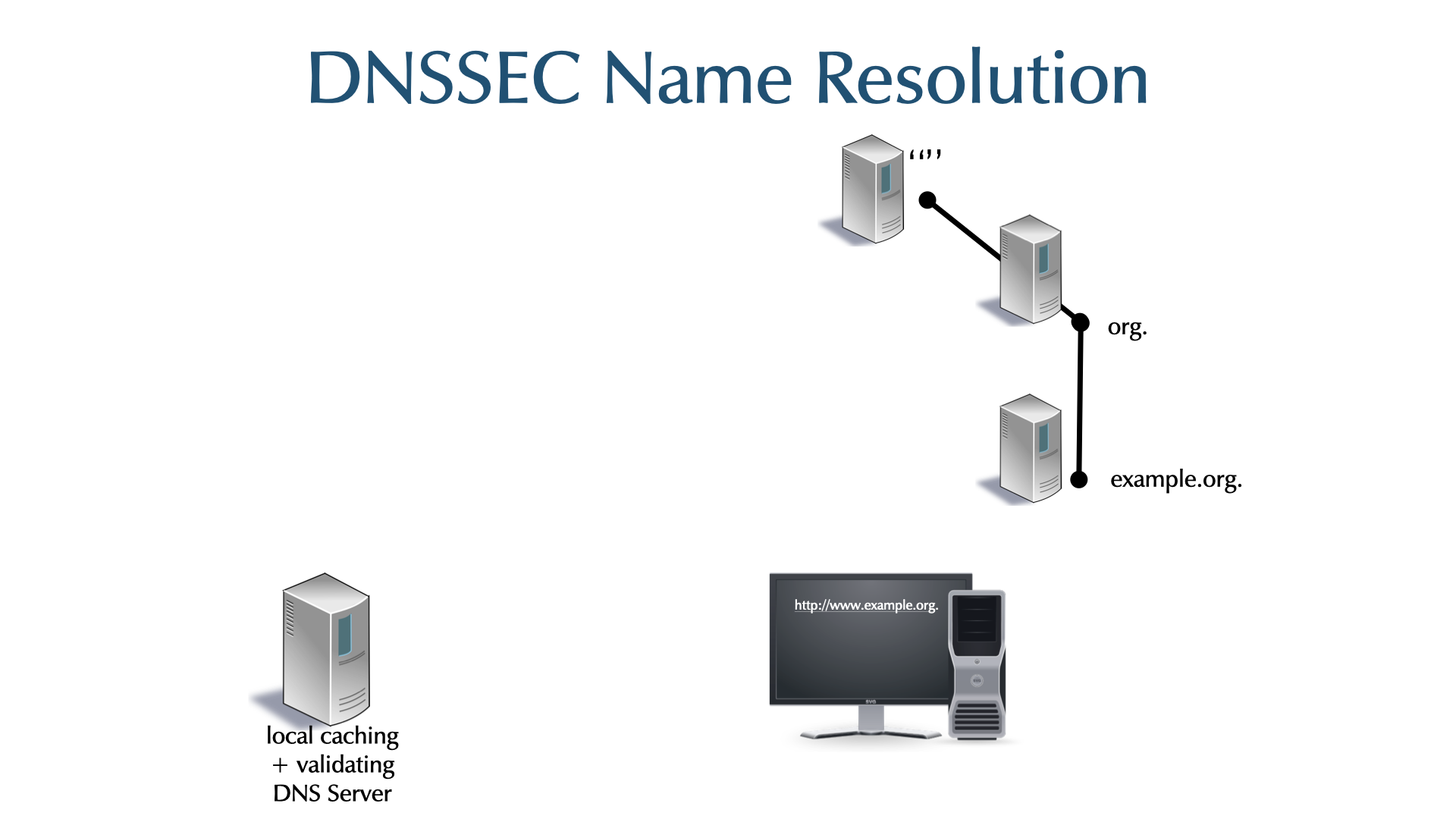

8 DNSSEC validation

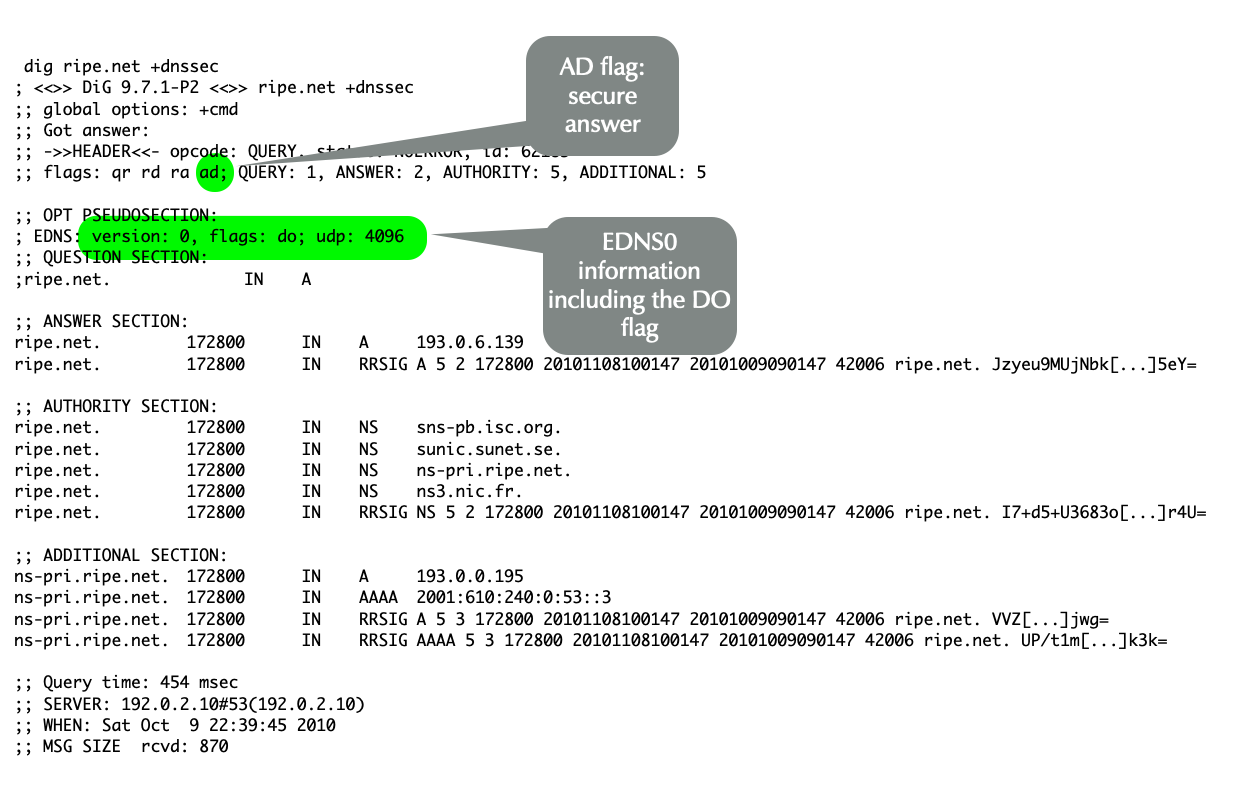

8.1 DNSSEC in DNS Messages

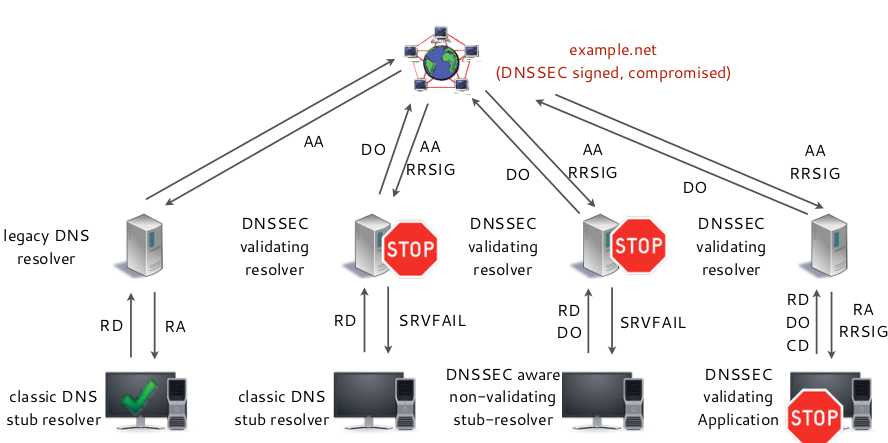

- Even if a client does not explicitly request DNSSEC by setting the

DOflag in a recursive query, it is protected.- It benefits from DNSSEC, if its recursive server is configured for DNSSEC.

- The recursive server will return SERVFAIL if the requested RRSet proves unauthentic.

DOFlag: DNSSEC OK- The client is requesting the authoritative server to return the

RRSIG together with the queried RRSet.

- The client is commonly a resolver, but it could be a stub resolver or application.

- With EDNS the client also announces the UDP packet size it will handle.

- If the

DOflag is not set, RRSIGs are not returned by authoritative servers.

- The client is requesting the authoritative server to return the

RRSIG together with the queried RRSet.

ADFlag: Authentic Data- The resolver uses the

ADflag to inform a DNSSEC-aware client that it has successfully authenticated the RRSet. - An unauthentic RRSet will not be sent to the client; the resolver

returns

SERVFAIL.- Without DNSSEC,

SERVFAILmeans an authoritative server isn't responding.

- Without DNSSEC,

DOis client (resolver) to authoritative server, andADis recursive resolver to client.

- The resolver uses the

CDFlag: Checking Disabled- An application or stub resolver can tell the recursive server that it will validate the DNSSEC information itself.

- This is ideal where the recursive server can't be trusted.

- A recursive server is often run by a third party, e.g. an ISP or Internet cafe, and therefore is not inherently trustworthy.

- Additionally, the connection between the application or stub resolver with even a trusted recursive server, is likely insecure.

- There is no way for a client to force a recursive resolver to use, or not use, DNSSEC.

CDwithDOtells the recursive resolver to return the queried RRSet regardless of its authentication.- The

CDflag is an excellent debugging resource. - For example, if a client receives SERVFAIL, requerying with dig can indicate if the problem is DNSSEC or not.

$ dig example.com +cdflag

- The

COFlag - Compact Answers OK- Compact Denial of Existence is a new DNSSEC extension that

allows authenticated Denial of Existence with

NSEC(and optionallyNSEC3) for online signer- it also prevents Zone Walking, even with

NSECrecords - the

COFlag is send by an DNS resolver towards authoritative DNS-servers (primary or secondary) to inform the receiver that the sender does understand the new compact answers - the

COFlag is encoded inside the EDNS-Flag-space (alongside theDO-Flag)

- it also prevents Zone Walking, even with

- Details: RFC 9824 Compact Denial of Existence in DNSSEC (September 2025)

- Compact Denial of Existence is a new DNSSEC extension that

allows authenticated Denial of Existence with

8.2 Basics of DNSSEC validation

- When the validator gets an RRSIG in a response, it needs the DNSKEY

and DS RR to authenticate.

- If validation fails, the signed RRs are discarded, and SERVFAIL error is returned to the client.

- If no appropriate trust anchor exists, the RRSIG is ignored.

- If the chain of trust is broken the signature is ignored.

- The steps in the following animation are simplified.

- It only shows validation using one key per zone (SSK/CSK).

- Commonly, a zone has ZSK & KSK, so there are additional steps.

8.3 Building a validating DNS Resolver

- Work on the

dnsrNNvirtual machine (DNS resolver server) - Obtain root privileges

$ sudo -s

- Install BIND 9

% dnf install bind

- Enable and start BIND 9

% systemctl enable --now named

- Check that BIND 9 is running without errors

% rndc status % systemctl status named

- Try if our BIND 9 works as a DNS resolver

$ dig @localhost switch.ch

8.4 Optimizations to the default configuration

- Work on the

dnsrNNvirtual machine (DNS resolver server) - Let's tweak the configuration file

/etc/named.conffor a resolver DNS server. Add the following new lines in theoptionsblock in the/etc/named.conffile:options { [...] dnssec-validation auto; server-id none; version none; hostname none; recursive-clients 32768; tcp-clients 1024; max-clients-per-query 1024; fetches-per-zone 2048; fetches-per-server 4096; edns-udp-size 1232; max-udp-size 1232; minimal-responses yes; querylog no; max-cache-size 2147483648; }; - The values above are for an ISP level DNS resolver. They should work for a broad range of DNS resolver machines, from small to very large.

- The new configuration statements:

dnssec-validation auto;enables DNSSEC validation via the built in trust anchor for the Internet Root-Zone. If DNSSEC is used in an closed private DNS system (not connected to the Internet), dedicated DNSSEC trust anchor must be configured.- server-id none: disable returning the server's hostname on the

query

dig @ip-of-server ch TXT hostname.bind - version none: disable returning the BIND 9 version number on

the query

dig @ip-of-server ch TXT version.bind - recursive-clients: number of concurrent DNS queries over UDP that are allowed from clients

- tcp-clients: number of concurrent DNS queries over TCP that are allowed from clients

- max-clients-per-query 1024: rate-limiting - number of concurrent clients that can request the same query

- fetches-per-zone: rate-limiting - maximum number of concurrent DNS queries inside one zone

- fetches-per-server: rate-limiting - maximum number of concurrent DNS queries towards one authoritative DNS server

- edns-udp-size: maximum UDP answer size requested from authoritative servers

- max-udp-size: maximum UDP answer size when sending answers to clients

- minimal-responses yes: only fill the authority and additional sections when necessary by the DNS protocol

- querylog no: disable query logging on start/restart even if configured. Query logging slows down the DNS resolver

- max-cache-size 2147483648: use a maximum of 2GB for the DNS cache. A larger cache often has a negative impact on the DNS resolvers performance. If unsure, test with a performance benchmark.

- Check the configuration with

named-checkconfand reload the BIND 9 configuration withrndc reconfig - Make sure that the DNS resolver still does resolve DNS names in the Internet

8.5 Extended DNS errors (EDE)

- RFC 8914 - Extended DNS Errors defines a way to deliver additional

error information in an DNS response. It is implemented in

digsince version BIND 9.16.4. BIND 9.18 and other open source DNS-Server support EDE-Messages, as well as some DNS resolver on the Internet (like Cloudflare):

$ dig lame.defaultroutes.org soa @1.1.1.1 < ; <<>> DiG 9.18.41 <<>> lame.defaultroutes.org soa @1.1.1.1 ;; global options: +cmd ;; Got answer: ;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: SERVFAIL, id: 29410 ;; flags: qr rd ra; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 0, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1 ;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION: ; EDNS: version: 0, flags:; udp: 1232 ; EDE: 22 (No Reachable Authority): (at delegation lame.defaultroutes.org.) ;; QUESTION SECTION: ;lame.defaultroutes.org. IN SOA ;; Query time: 705 msec ;; SERVER: 1.1.1.1#53(1.1.1.1) (UDP) ;; WHEN: Mon Nov 03 13:19:33 CET 2025 ;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 94

9 DNSSEC Keys

9.1 Algorithms for DNSSEC

DNSSEC keys can be generated with different crypto algorithms. Some of these algorithms are obsolete and deprecated, others are not (yet) widely supported by deployed DNS software to be useful

| Algorithm | No. | Note |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | deprecated, not implemented | |

| 5 | not recommend, deprecated for DNSSEC signing, not supported in Red Hat Enterprise Linux 9 (and up) | |

| RSASHA256 | 8 | recommended |

| RSASHA512 | 10 | large keys, large signatures, risk of UDP fragmentation or TCP fallback |

| 3 | deprecated, slow validation, no extra security | |

| 12 | deprecated | |

| ECDSA | 13/14 | small signatures, read RSA vs ECDSA for DNSSEC |

| ED448/ED25519 | 16/15 | not supported by legacy resolver RFC 8080 / RFC 8032 Edwards-Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (EdDSA) / Assessing DNSSEC with EdDSA |

| SM2SM3 | 17 | SM2 and SM3 are cryptographic algorithms that are national standards for China, as well as ISO/IEC standards RFC 9563 |

| GOST-2012 | 23 | GOST R 34.10-2012 and GOST R 34.11-2012 are Russian national standards. Their cryptographic properties haven't been independently verified. RFC 9558 |

9.2 DNSSEC key sizes for RSA algorithm

- Every additional bit increases the strength of a DNSSEC against brute-force attacks to break the key

- Double the RSA key size results in

- Generating signatures is up to eight times more work

- Validation of DNSSEC signatures inside an DNS resolver up to 4 times more work

- Size of key and signature records increases and can create operational issues

9.2.1 Problems with large DNS response messages

- Fragmentation of IPv4 and IPv6 UDP messages

- Hurts performance

- Fragmented IPv6 packets (containing a fragment header) could be blocked on the Internet backbone

- Enables UDP fragmentation attacks against non-validating DNS resolver

- DNS amplification attacks

The goal should be that the DNSKEY RRSet during an KSK rollover (including perhaps an emergency KSK) stays below 1232 byte

9.3 KSK and ZSK

- For organizational reasons, DNSSEC splits the chain of trust inside a DNS zone onto two different keys: the Key-Signing-Key (KSK) and the Zone-Signing-Key (ZSK)

9.3.1 KSK:

- The KSK generates only one signature: the signature over the DNSKEY record (RRset)

- The hash of the KSK is stored in the parent zone as the DS record. This hash is used to close the chain of trust from the parent zone to the DNSSEC signed zone. Each time the KSK in the DNSSEC signed zone is changed, the DS record in the parent zone must be replaced. The KSK has therefore a dependency on the parent zone.

- Because of this dependency with the parent zone, the KSK is usually a stable and strong key and not rolled often

9.3.2 ZSK:

- The Zone-Signing-Key does not have dependencies to external resources and can be rolled at any time

- Usually the ZSK is rolled often (and automatically), so the key does not need to be particularly strong

9.4 BIND 9: KSK/ZSK signature over the DNSKEY record set

- For historical reasons, BIND 9 generates two signatures over the

DNSKEY record set:

- one signature generated with the KSK (required)

- one signature generated with every active ZSK (optional)

- This can generate larger than good DNSKEY record answer messages

- BIND 9 can be configured to only generate a signature using the KSK

options { [...] dnssec-dnskey-kskonly yes; };

9.5 Lifetimes of DNSSEC keys

- DNSSEC keys have an organisational lifetime (there is no technical

limit on the lifetime, unlike with X.509 TLS certificates)

- the administrator responsible for a DNSSEC-signed zone can decide when to change the DNSSEC keys

- Renewing the DNSSEC key material of a zone is called a key rollover

- Keys with weak algorithms or short key lengths should be changed

(rolled) in shorter intervals

- 1024bit RSASHA256 -> 30 days (ZSK)

- 1536bit RSASHA256 -> 120 days (ZSK)

- 2048bit RSASHA256 -> 360 days (KSK)

- 2560bit RSASHA256 -> 720 days+ / 2 years+ (KSK)

9.6 DNSSEC Signer "Best-Practices"

- Zones with high security requirements should keep the DNSSEC keys

"offline"

- this requires manual DNSSEC signing

- Keys can be stored securely in Hardware Security Modules (HSM)

- HSM selection criteria for DNSSEC signing

- Number of key storage slots

- Timely support for new operating system releases (Linux distribution)

- Timely support for new OpenSSL releases

- Stability of the HSM-Driver

- Zones with medium to low security requirements should use a

hidden-primary DNSSEC signer configuration

- The DNSSEC signing authoritative server is not exposed to the Internet, it will not receive DNS queries

- DNS secondary authoritative servers in the Internet will receive the DNSSEC signed zone from the hidden DNSSEC signer through DNS zone transfer

- The DNSSEC key material is secured with operating system level permissions

- With full automation of DNSSEC key-rollovers, the DNS server administrators don't need access to the DNSSEC keys

- Login and access to the DNSSEC key files should be audited (Logging online and towards a remote log server)

- Zone content can be split across multiple zones or DNS server

with DNS delegation

- Every zone can have a different DNSSEC security level

- Example: main zone

example.comsigned via a hidden-signer (keys not exposed to the Internet) has a sub-zone with e-mail address hashes (OPENPGPKEY and SMIMEA) in the zonesecuremail.example.com) which is secured with NSEC3-NARROW scheme and keys that are online on every authoritative server

10 DNSSEC signing with BIND 9

10.1 Manual zone signing

- Since BIND 9.6 zones can be signed manually (BIND 9.6 was the first version to support the new DNSSEC version)

- Benefits:

- The signing can be done offline on a machine not connected to any network, BIND 9 does not need to be running on the signing machine

- The DNSSEC private keys can be stored on security devices such as Hardware Security Modules (HSM) and can be encrypted

- The generated DNSSEC signed zone files are universal and can be used in any DNS server that supports DNSSEC signed zones

- The parameters of the signing process can be tuned

- Drawbacks:

- Manually signed zones need to be refreshed (re-signed) periodically so that the signatures do not expire

- Any automation must be done through custom scripts

10.2 Exercise: an authoritative DNS Server

- Use your virtual lab machine,

nsNNa.dnslab.org(primary authoritative) - Obtain root privileges

$ sudo -s

- Install BIND 9 and start the BIND 9 process

% dnf install bind % systemctl enable --now named

- Open port 53 (DNS) in the firewall

% firewall-cmd --permanent --zone=public --add-service=dns % firewall-cmd --reload

- Check the version and the compile time configuration of the

installed BIND 9 server

% named -V

- Open the BIND 9 configuration file

/etc/named.confwith a text editor% $EDITOR /etc/named.conf

- Disable recursion

options { [...] recursion no; [...] }; - Adjust the

listen-ondirectives to listen toanyinterfaceoptions { [...] listen-on { any; }; [...] }; - Permit queries from anywhere

options { [...] allow-query { any; }; [...] }; - Add a sensible logging configuration for an authoritative BIND 9 server (here's a template you can use).

- Add a new primary zone definition at the end of the configuration

file for the zone

zoneNN.dnslab.org. ReplaceNNwith your participant numberzone "zoneNN.dnslab.org" IN { type primary; file "zoneNN.dnslab.org"; }; - Create a new zone file for the zone

zoneNN.dnslab.orgin the directory/var/named. It is important to use low Time-To-Live values in our lab zones (recommended: 60 seconds), else the key rollover of the DNSSEC keys later in the training will take too long time.$ORIGIN zoneNN.dnslab.org. $TTL 60 @ IN SOA nsNNa.dnslab.org. hostmaster 1001 1h 30m 41d 60 IN NS nsNNa.dnslab.org. IN TXT "Zone zoneNN.dnslab.org" IN MX 10 mail.zoneNN.dnslab.org. mail IN A xxx.xxx.xxx.xxx IN AAAA xxxx:xxxx:xxxx:xxxx:xxxx:xxxx:xxxx:xxxx - Replace

NNwith your participant number. Add the IPv4 and IPv6 address of your VM (seehostname -Ifor the addresses)% $EDITOR /var/named/zoneNN.dnslab.org

- Check the BIND 9 configuration file for errors

% named-checkconf -z

- If no errors are reported, reload the new zone into the BIND 9

server (via

rndc)% rndc reconfig

- Test of your DNS server will respond to queries for this zone

$ dig @127.0.0.1 zoneNN.dnslab.org SOA

- Use an external DNS resolver (Quad9 in this example) to resolve

data from the new DNS zone

$ dig @9.9.9.9 zoneNN.dnslab.org SOA

10.3 Exercise: Signing BIND 9.6 style (manual signing)

- Create a Zone Signing Key (ZSK), RSASHA256 Algorithm and 1024 bit length

% mkdir -p /etc/bind/keys % cd /etc/bind/keys % dnssec-keygen -a RSASHA256 -b 1024 zoneNN.dnslab.org

- Create a Key Signing Key (KSK), RSASHA256 Algorithm and 2048 bit length

% dnssec-keygen -a RSASHA256 -b 2048 -f KSK zoneNN.dnslab.org

- Add the public part of the ZSK and KSK to the zone file and

manually increment the SOA serial number (in a text editor)

% cat KzoneNN.dnslab.org.+008+*.key >> /var/named/zoneNN.dnslab.org % $EDITOR /var/named/zoneNN.dnslab.org

- DNSSEC sign the zone

% dnssec-signzone -o zoneNN.dnslab.org \ -k KzoneNN.dnslab.org.+008+(KSK).private \ /var/named/zoneNN.dnslab.org \ KzoneNN.dnslab.org.+008+(ZSK).private - Adjust the zone definition in the Bind 9 configuration file to now

load the signed version of the zone file

zone "zoneNN.dnslab.org" { type primary; file "zoneNN.dnslab.org.signed"; }; - Test the BIND 9 configuration, and if no errors are shown, reload

the signed zone into BIND 9

% named-checkconf -z % rndc reconfig

- Check locally if DNSSEC records are returned from our DNS server

$ dig @localhost zoneNN.dnslab.org SOA +dnssec +multi

- The DS record for the zone can be found in the file

dsset-zoneNN.dnslab.orgin the directory where the zone has been signed. Copy the DS record onto the machine of the trainer (usingscp, usernameuserand passwordDNSandBIND. The trainer is operating the parent zone of your zone and will add the DS record there to close the chain of trust.% cat dsset-zoneNN.dnslab.org. % scp dsset-zoneNN.dnslab.org. user@ns01a.dnslab.org:.

- Wait for the DS record to be published in the parent zone

- Now test DNSSEC validation against your DNS resolver machine

$ dig @<IP-of-resolver> zoneNN.dnslab.org SOA +dnssec +multi

- Query the DS record from the parent

$ dig @<IP-of-resolver> zoneNN.dnslab.org DS +dnssec

- Make a small change to your zonefile (add or change a TXT record),

increment the SOA serial (or use the command

dnssec-signzonewith the parameter-N unixtime) - Test the zone file

% named-checkzone zoneNN.dnslab.org /var/named/zoneNN.dnslab.org

- Re-Sign the zone

% dnssec-signzone -o <zonenname> -k <KSK-private-file> <zonefile> \ <ZSK-private-file> - Load the newly signed zone in BIND 9

% rndc reload zoneNN.dnslab.org

- Check for the changes you made, are they visible? (Do you still see

the AD-Flag?). Adjust the query below to match your changes to the

zone file:

$ dig TXT text.zoneNN.dnslab.org +dnssec +multi

11 DNSSEC Key and Signing Policy

- BIND 9.16 has introduced a new

dnssec-policyfeature as a further step in automation - Configuring a zone to use KASP (Key And Signing Policy) can be

as easy as

zone "example.net" { type primary; dnssec-policy default; ... }; - Requirements

- One of the following

inline-signing yes; // manual edited zone files update-policy local; // dynamic update zone files

- One of the following

- Benefits

- More intuitive and a higher level of automation

- Several vendors use KASP (Knot, OpenDNSSEC)

- Robust

- No need to rely on metadata added by humans

- Use key timing state machine

11.1 Default policy

- Single CSK ("common signing key", also called a SSK - "single signing key")

- ECDSAP256SHA256 (algo 13) with unlimited lifetime

- RRSIG validity 14 days, refreshed 5 days before expiration

- NSEC

- Key timings:

- DNSKEY TTL: 3600, max zone TTL: 86400 (1 day)

- Key publish and retire safety times: 3600 (1 hour)

- Propagation delay: 300 (5 minutes)

- Parent timings

- DS TTL: 86400 (1 day)

- Propagation delay: 3600 (1 hour)

- Prevent policy changes on upgrade by using an explicitly defined dnssec-policy, rather than

default

11.2 Additional configuration of custom policy

dnssec-policy "one" {

keys {

ksk lifetime 365d algorithm rsasha256 4096;

zsk lifetime 60d algorithm rsasha256 1024;

};

dnskey-ttl 600;

publish-safety PT2H;

signatures-refresh 7d;

nsec3param iterations 0 optout no salt-length 0;

};

11.3 Key-and-Signing-Policy (KASP) syntax

dnssec-policy <string> {

dnskey-ttl <duration>;

keys { ( csk | ksk | zsk ) [ ( key-directory ) ]

lifetime <duration_or_unlimited> algorithm <string> [ <integer> ]; ...

};

max-zone-ttl <duration>;

nsec3param [ iterations <integer> ] [ optout <boolean> ] [ salt-length <integer> ];

parent-ds-ttl <duration>;

parent-propagation-delay <duration>;

publish-safety <duration>;

purge-keys <duration>;

retire-safety <duration>;

signatures-refresh <duration>;

signatures-validity <duration>;

signatures-validity-dnskey <duration>;

zone-propagation-delay <duration>;

};

11.4 A real world custom DNSSEC policy

- A KSK with ECDSAP256SHA256 and no automatic key rollover

- A ZSK with ECDSAP256SHA256 and a rollover interval of 30 days

- Signatures are valid for 10 days

- Signatures will be refreshed after 8 days (2 day buffer)

- TTL of DNSKEY records is 2 hours

- Max TTL of other records in the zone is 1 day

- DNSSEC keys will be published one hour after they have become valid (publish-savety)

- DNSSEC keys will be kept in the zone one our after deactivation (retire-safety)

- Expired DNSSEC keys will be removed after 90 days

- Zone transfer between primary and secondary servers is 5 minutes (zone-propagation-delay)

dnssec-policy "example.eu" {

dnskey-ttl 2h;

keys { ksk lifetime unlimited algorithm ECDSAP256SHA256;

zsk lifetime P30D algorithm ECDSAP256SHA256;

};

max-zone-ttl 1d;

publish-safety 1h;

purge-keys P90D;

retire-safety 1h;

signatures-refresh 8d;

signatures-validity 10d;

signatures-validity-dnskey 10d;

zone-propagation-delay 300;

};

12 Easy DNSSEC with BIND "default-policy"

- Using DNSSEC policy configuration (available since BIND 9.16) makes DNSSEC easy to deploy

- BIND automatically creates the DNSSEC keys, signs the zone and keeps the signatures updated

- Policy

defaultcauses the zone to be signed with a single combined signing key (CSK) using algorithm ECDSAP256SHA256; this key will have an unlimited lifetime (no key rollover).

12.1 DNSSEC signing the zone

- We work on the primary authoritative server

- Create a new zone file with the name

p.zoneNN.dnslab.orgin/var/named/. The zone should containSOA,NSand oneTXTrecord. TheNSrecord should point tonsNNa.dnslab.org$ORIGIN p.zoneNN.dnslab.org. $TTL 60 @ IN SOA nsNNa.dnslab.org. hostmaster.zoneNN.dnslab.org. 1001 1h 2h 41d 60 IN NS nsNNa.dnslab.org. IN TXT "This is a zone with BIND 9 default policy" - Open the file

/etc/named.confin an editor and add a zone block withdnssec-policy default;line to the configuration::zone "p.zoneNN.dnslab.org" { type primary; file "p.zoneNN.dnslab.org"; dnssec-policy default; inline-signing yes; }; - Check the configuration and reload BIND 9

% named-checkconf -z % rndc reconfig

- You should now see key files and additional zone-files in the BIND

9 home directory

% ls -l /var/named

- Test if the DNS server returns DNSSEC resource records

$ dig @localhost p.zoneNN.dnslab.org +dnssec +multi $ dig @localhost p.zoneNN.dnslab.org DNSKEY +dnssec +multi

- Resolve a domain name

p.zoneNN.dnslab.orgfrom your zone on your resolver machine. Does it show theAD-Flag? What might be missing?

12.2 Add the DS-Record from your child-zone to your parent zone

- Your zone

zoneNN.dnslab.org.in the parent ofp.zoneNN.dnslab.org - In order to close the chain of trust, you must publish the

DS-record for

p.zoneNN.dnslab.orgin your own zonezone.dnslab.org. The DS-record contains the hash of the main key of the zone (the KSK or CSK/SSK). The CSK can be found in/var/named/Kp.zoneNN.dnslab.org.+013+<CSK-ID>.key, and the DS-Record can be created with (replace ZZZZZ with the key-id):% dnssec-dsfromkey /var/named/Kp.zoneNN.dnslab.org.+013+ZZZZZ.key

- Add a delegation NS-Record into the parent zone

zoneNN.dnslab.orgp.zoneNN.dnslab.org. IN NS nsNNa.dnslab.org.

- Add the DS-Record to the zone

zoneNN.dnslab.org, increment the SOA serial number, resign thezoneNN.dnslab.org(the parent zone that does not use automation) withdnssec-signzone(same command used in the previous exercises). - Reload the parent zone

% rndc reload zoneNN.dnslab.org

- Try again to query a name from the zone

p.zoneNN.dnslab.org, theADflag should now appear.

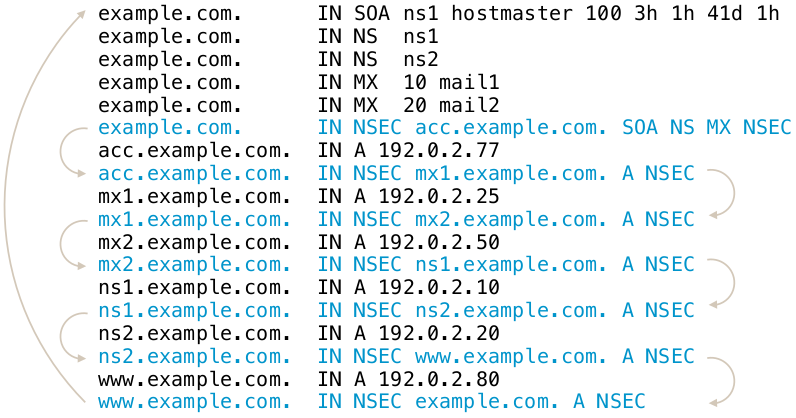

13 NSEC vs. NSEC3

13.1 Authenticated Denial of existence - NSEC vs. NSEC3

- The RRSIG records in DNSSEC secure the positive answers from DNS (answers to queries where DNS records exist)

- But also negative answers need to be protected

- without protection for negative answers, attackers could spoof negative answers to launch denial-of-service attacks. The attacker can make DNS clients believe that a DNS resource does not exist

- DNS knows two kinds of negative answers: NXDOMAIN and NODATA/NXRRSET

- NXDOMAIN = the requested domain name does not exist

- NODATA/NXRRSET = the requested domain name does exist, but the requested record type does not exist for this name

- DNS error messages such as SERVFAIL, FORMERR or REFUSED cannot be secured with DNSSEC (these errors indicate errors in the protocol or in the DNS server infrastructure). If the protocol is broken, DNSSEC can't work either.

- The solution: the NSEC records in the DNSSEC signed zone create a

list of all existing data in the zone (domain names and records

types for the domain names)

- When returning a negative answer, the DNS server returns the negative answer containing the NSEC record (plus a signature for the NSEC record) which proves that the requested data does not exist in DNS

13.2 Issues with NSEC

- The NSEC record is an elegant solution to the problem, but it has

drawbacks:

- It is now possible for outsiders to list the complete zone contents by following the NSEC record chain. This is called zone walking.

- For most zones this is not a big problem, as the DNS zone content is public anyway (SOA, NS records, WWW-A, MX records)

- But it can be an issue for zones with sensitive content (email addresses, hostnames of critical infrastructure, new product names that should no go public yet)

- Operators of TLDs zones stay away from DNSSEC with NSEC, as it allows outsiders to record all changes to the TLD zone (new delegations and delegation removals)

- The new compact authenticated denial of existance standard (RFC 9824) solves this issue.

- Example of zone walking:

$ ldns-walk paypal.com

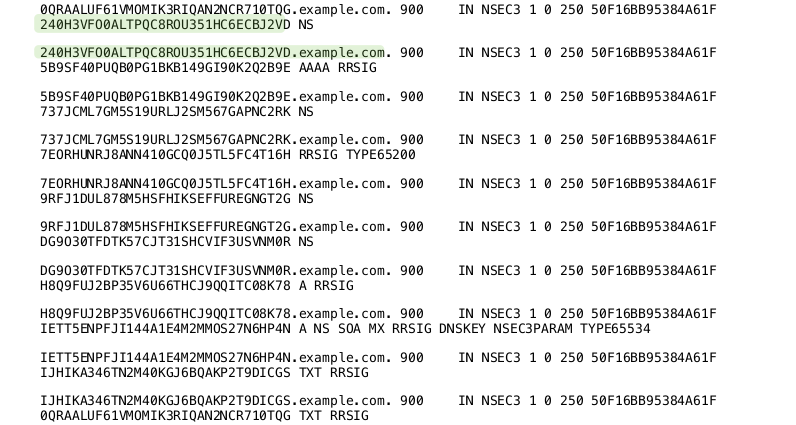

13.3 The NSEC3 record

- RFC 5155 (2008) defines the NSEC3 record as an alternative to NSEC

- All modern DNS servers support NSEC3

- The NSEC3 record works similarly to NSEC, with the difference that the link between the owner names is done using SHA1 hashes of the domain names instead of the clear text names

- NSEC3 makes it harder, but not impossible, to list the zone content

13.4 NSEC3 Chain

13.5 NSEC3-Parameter

- The NSEC3 record contains a number of parameters used for the

NSEC3 operation

- The hashing algorithm used (currently only SHA1 is defined)

- Flags: allows for DNSSEC opt-out in delegations.

- Number of hash iterations

- A salt value

13.6 NSEC3-Parameter Record

- Every zone with NSEC3 records contains an

NSEC3PARAMrecord. This record holds information needed by authoritative DNS servers to generate NSEC3 records for negative answers - Example: (SHA1, no flags, 20 iterations, salt value "ABBACAFE")

nsec3.dnslab.org. 0 IN NSEC3PARAM 1 0 20 ABBACAFE

13.7 NSEC3 iterations and salt

- The idea of the hash iterations in the NSEC3PARAM record was to

allow the operator of the zone to fine tune the work required for

calculating the hash

- A higher number of iterations should make it harder for attackers to brute force break an NSEC3 domain name

- A higher number also creates more CPU load for DNS resolvers that validate the NSEC3 records, making DNS name resolution slower

- The iteration parameter of an NSEC3 signed zone should be re-evaluated from time to time (yearly) to adjust the value for the technical progress

- The salt should make it impossible for an attacker to pre-calculate rainbow tables for the zone

- The salt is a hexadecimal number, every hex digit contains 4 bit of information

13.8 Problems with NSEC3

- The iterations had more an negative impact on the CPU load of the authoritative DNS servers than preventing attacks

- The salt is not really needed, as each zone naturally has unique hashes so that a rainbow table for multiple zones is not possible

13.9 RFC 9276 - Guidance for NSEC3 Parameter Settings

- RFC 9276 - Guidance for NSEC3 Parameter Settings (Best current practice) gives updates guidelines for NSEC and NSEC3 deployments

- The iterations value should be set to

0(meaning 1 iteration of SHA1 hashing)- DNSSEC responses containing NSEC3 records with iteration counts greater than 150 are now treated as insecure by major DNS resolvers!

- As NSEC3 zones are inherently salted, the salt parameter should be

set to

- - The current recommendation for NSEC3PARAM is

1 0 0 -(SHA1 Hash, no flags, 1 iteration, no salt)

13.10 NSEC3 needed?

- Most DNS zone can work with NSEC instead of NSEC3

- Don't store names in DNS that should be secret (internal names, product names etc)

- DNS is a service to publish data, not for hiding data

13.11 NSEC3 Narrow-Mode

- RFC 7129 (also RFC 4470 and RFC 4471) describe a special variant of

NSEC3 usage, called the narrow mode

- With narrow mode, the NSEC3 records are not pre-calculated when

the zone is signed, but they are created on the fly whenever a

negative response is needed

- To be able to calculate the signatures for such answers, every authoritative DNS server for the zone must have access to the private DNSSEC keys (at least the ZSK)!

- With narrow mode, the NSEC3 records are not pre-calculated when

the zone is signed, but they are created on the fly whenever a

negative response is needed

- With NSEC3 narrow mode, the DNS server does not return an NSEC3

chain of existing records, but a synthetic NSEC3 record that proves

that the requested name does not exist

- This prevents zone walking, as the number of possible NSEC3 records returned is near infinite. It will exhaust the memory of the attacker that will try to store this NSEC3 chain

- Known implementations:

- Phreebird (Dan Kaminski, Proof-of-Concept, not maintained)

- PowerDNS Authoritative

- Cloudflare CDN NSEC3 Narrow-Mode (closed source implementation)

13.12 Exercise: sign a static zone with NSEC3 instead of NSEC

- Sign a zone with NSEC3 (

saltmust be a hexadecimal number with even count of octets (8,10,12 …) or a single dash (-))% dnssec-signzone -3 <salt> -H <iterations> -o zoneNN.dnslab.org \ -k <KSK-private-file> zoneNN.dnslab.org \ <ZSK-private-file>

14 DNSSEC Applications

- Securing E-Mail with SPF/DKIM/DMARC: https://switch.dane.onl

- Securing Security with DANE (x509 trust from DNS): https://switch-lausanne.dane.onl

15 DNSSEC Key-Rollover

15.1 Why Keyrollover

- The DNSSEC key material is public

- Including the signatures and the matching clear text (DNS record sets)

- The private key can get in un-authorized hands

- By accident

- By attacks on the signing server/HSM

- When using online-signing, the private keys must be live on the signing DNS server

- The key length or the algorithm used is not considered secure for a longer amount of time (for example 1024bit RSA keys)

15.2 The Challenges

- The DNS is not consistent

- DNS zone data can differ for some time between authoritative server of the same zone (delay in zone transfer)

- DNS data is cached in DNS resolvers, operating systems, and applications

- During a DNSSEC key-rollover, the chain of trust must be un-broken at all times from all vantage points of the Internet

15.3 DNSSEC Keyrollover Documentation

- RFC 6781 - DNSSEC Operational Practices, Version 2

- RFC 7583 - DNSSEC Key Rollover Timing Considerations

15.4 Key rollovers, when and how often?

- DNSSEC keys do not have a technical lifetime, they don't expire

- The operational life time of DNSSEC keys is decided by the responsible administrator(s) and can be changed at any time

- The DNSSEC community has different views on KSK key rollovers

- Often and regularly

- Often but irregular (to not give attackers information when the system might be more vulnerable due to the key rollover)

- Only if there is evidence that the key has been compromised or stolen

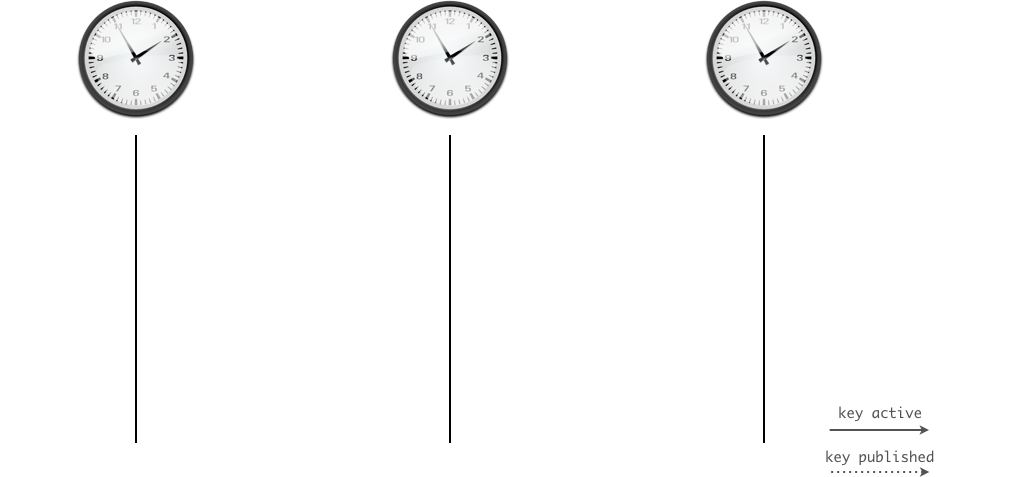

15.5 ZSK Rollover

- The Zone-Signing-Key has no dependencies to external resources (such as the parent zone)

- A ZSK Rollover can be started at any time

- The 'pre-publication' rollover scheme is used for ZSK rollover

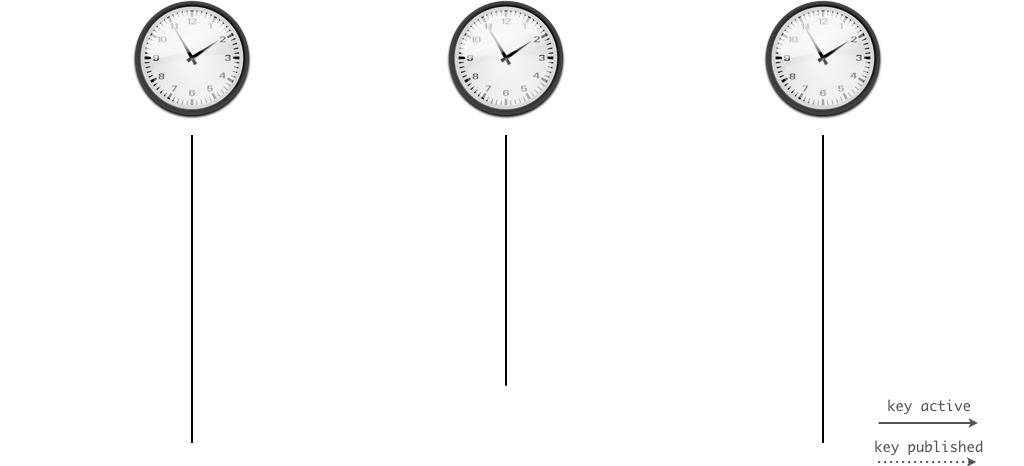

15.5.1 ZSK - pre-publication - Step 1

- Create a new ZSK key pair

- Publish the public part of the new key (DNSKEY) of the ZSK in the zone

- The current/old ZSK is kept in the zone

- The zone is signed with the current/old (not the new) ZSK and KSK

15.5.2 ZSK - pre-publication - Step 2

- Wait for the zone with the new ZSK be visible on all authoritative DNS servers of the zone (zone transfer)

- Wait for the TTL of the DNSKEY RRset (+ some buffer for security)

- Now we can be sure the new ZSK DNSKEY record is in all caches (DNS resolvers, operating systems, applications)

15.5.3 ZSK - pre-publication - Step 3

- Sign the zone with the new ZSK

- The new ZSK is now active, the old ZSK is now retired

- The old ZSK will be kept in the zone for now (it is needed to validate old signatures that still exist in the caches in the network)

15.5.4 ZSK - pre-publication - Step 4

- Wait for the new zone version with the signatures from the new ZSK to be visible on all authoritative DNS servers of the zone (zone transfer)

- Wait for the largest TTL in the zone (plus some buffer)

- Now the signatures created by the old ZSK are expired from the caches, and the new signatures are available

15.5.5 ZSK - pre-publication - Step 5

- Remove the old ZSK from the DNSKEY record set of the zone

- Continue signing the zone with the new ZSK

15.5.6 ZSK - pre-publication in pictures

15.6 Exercise: ZSK Rollover

- In this exercise we will perform a ZSK-Rollover on the manually-signed

zone

zoneNN.dnslab.org. This will be a pre-publish roll-over. - Step 1: create a new ZSK key-pair and note down it's Key-ID

% cd /etc/bind/keys % dnssec-keygen -a RSASHA256 -b 1024 zoneNN.dnslab.org

- Publish the public part of the new key in the zone. Make sure to

use

>>when using shell redirection.% cat KzoneNN.dnslab.org.+008+<ID-of-the-new-ZSK>.key >> /var/named/zoneNN.dnslab.org

- Increment the SOA serial of the zone (or use the Unixtime as the SOA-serial when signing the zone)

- Sign the zone with the old/current ZSK (to publish the new ZSK)

% dnssec-signzone -N unixtime -o zoneNN.dnslab.org \ -k <KSK-private-file> \ /var/named/zoneNN.dnslab.org \ <ZSK-private-file>

- Load the signed zone in the BIND DNS server and check that all

secondaries have loaded the new zone (check the SOA serial number)

% rndc reload $ dig zoneNN.dnslab.org +nssearch

- Wait for the TTL of the DNSKEY record-set (60 seconds in this case)

- Increment the SOA serial of the zone (or use the Unixtime), then

sign the zone (without any other change) with the new ZSK

% dnssec-signzone -N unixtime -o zoneNN.dnslab.org \ -k <KSK-private-file> \ /var/named/zoneNN.dnslab.org \ <NEW-ZSK-private-file> - Load the signed zone into the BIND 9 DNS server and check that all

secondaries have the new zone loaded (check SOA serial)

% rndc reload $ dig zoneNN.dnslab.org +nssearch

- Wait for the largest TTL used in the zone (should be 60 seconds in our case)

- Remove the old ZSK from the zone file

/var/named/zoneNN.dnslab.org, increment the SOA serial and sign the zone with the new ZSK:% dnssec-signzone -N unixtime -o zoneNN.dnslab.org \ -k <KSK-private-file> \ /var/named/zoneNN.dnslab.org \ <NEW-ZSK-private-file> - Load the signed zone into the BIND 9 DNS server and check that all

secondaries have the new zone loaded (check SOA serial)

% rndc reload $ dig zoneNN.dnslab.org +nssearch

- Check that the zone still is being DNSSEC validated (AD-Flag!)

$ dig zoneNN.dnslab.org SOA +dnssec +multi

- This is the end of the ZSK rollover

15.7 KSK Rollover

- The KSK has a dependency on its DS record in the parent zone

- For the KSK rollover we will use the 'double-signing' rollover scheme (the DNSKEY record set will get two signatures, from both, old and new, KSK)

15.7.1 KSK - double-signing - Step 1

- Create a new KSK key pair

- Publish the DNSKEY record of the new key in the zone

- Sign the DNSKEY RRset in the zone with both KSKs (old and new)

15.7.2 KSK - double-signing - Step 2

- Wait until the new zone content with the new KSK is visible on all authoritative DNS server of the zone

- Wait for the TTL of the DNSKEY RRSet (+ some buffer)

- The new KSK is now visible to all DNS clients (through DNS resolver caches)

15.7.3 KSK - double-signing - Step 3

- Send the new DS record to the operator of the parent DNS zone (usually through an API or through an Web-Interface)

- Wait for the DS record to be updated in the parent zone

- Wait for the TTL of the DS record in the parent zone (+ some buffer)

- The new DS record is now visible for all DNS clients

15.7.4 KSK - double-signing - Step 4

- Remove the old KSK from the DNSKEY record set of the zone

- Sign the zone with only the new KSK

- Wait and remove the old DS from the parent zone

15.7.5 KSK - double-signing in pictures

15.8 Exercise: KSK Rollover

- Use your virtual lab machine,

nsNNa.dnslab.org(primary authoritative) - Create a new KSK key pair

% cd /etc/bind/keys % dnssec-keygen -a RSASHA256 -b 2048 -f KSK zoneNN.dnslab.org

- Publish the new DNSKEY record in the zone, increment SOA-serial (or

use Unixtime), sign the zone with both KSK keys (old and new)

% cat KzoneNN.dnslab.org.+008+<ID-of-new-KSK>.key >> /var/named/zoneNN.dnslab.org % dnssec-signzone -N unixtime -o zoneNN.dnslab.org \ -k <OLD-KSK-private-file> \ -k <NEW-KSK-private-file> \ /var/named/zoneNN.dnslab.org \ <Current-ZSK-private-file> - Load zone into the BIND 9 server and verify that the zone still

validates (AD-Flag!)

% rndc reload $ dig zoneNN.dnslab.org SOA +dnssec +multi

- Submit the new DS to the parent zone

% scp dsset-zoneNN.dnslab.org. user@ns01a.dnslab.org:.

- Wait for the new DS record to be in the parent zone

$ dig zoneNN.dnslab.org DS

- Wait for the TTL of the DS record in the parent zone and the TTL of the DNSKEY record in the zone (whichever is larger)

- Remove the old KSK DNSKEY record from the zone file, increment the

SOA serial (or use the unixtime feature) and sign the zone with

only the new KSK and the current ZSK

% dnssec-signzone -N unixtime -o zoneNN.dnslab.org \ -k <NEW-KSK-private-file> \ /var/named/zoneNN.dnslab.org \ <Current-ZSK-private-file> - Load the signed zone into the BIND 9 server

% rndc reload

- Check that the zone still validates (AD-Flag!)

$ dig zoneNN.dnslab.org SOA +dnssec +multi

15.9 Algorithm Rollover

- An algorithm rollover is used when the DNSSEC key algorithm of the

zone needs to be changed

- e.g. when switching from RSASHA256 to ECDSASHA256

- During an algorithm rollover, the KSK and ZSK will be changed at

the same time using a double-signing rollover scheme

- During such a roll over, the zone should be monitored for failures and over sized DNS answer messages

- Link: DNSSEC algorithm rollover HOWTO by Tony Finch (Univ. of Cambridge)

15.10 Emergency Rollover Key

- In an emergency, time is at an essence

- To save time on an KSK rollover, step one (publication) can be done

ahead of time

- This published extra key is called the standby key

- It saves time, but makes the DNSKEY RRSet larger

- The standby key is not used during normal DNSSEC signing operation

- If there is a need to change the KSK in an emergency, the zone can almost immediately switch over to the standby key

- The standby key should be replaced (rolled) whenever the production KSK is rolled

16 KSK-2024 Root Zone KSK-Rollover

- The Key-Signing-Key of the Internet Root Zone will be rolled in

October 2026 (for the 2nd time in since the root has been DNSSEC

signed).

- Because this key is the trust-anchor for all of DNSSEC, and the public part or hash of that key has to be present in all DNS-resolver before the roll, special care must be taken by DNS resolver operators.

- The new KSK2024 key (Key-ID 38696) has been created in April 2024

and has been published in January 2025 inside the root DNS zone:

$ dig dnskey . +multi ; <<>> DiG 9.18.41 <<>> dnskey . +multi ;; global options: +cmd ;; Got answer: ;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 33764 ;; flags: qr rd ra ad; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 3, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1 ;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION: ; EDNS: version: 0, flags:; udp: 1232 ;; QUESTION SECTION: ;. IN DNSKEY ;; ANSWER SECTION: . 77796 IN DNSKEY 257 3 8 ( AwEAAaz/tAm8yTn4Mfeh5eyI96WSVexTBAvkMgJzkKTO iW1vkIbzxeF3+/4RgWOq7HrxRixHlFlExOLAJr5emLvN 7SWXgnLh4+B5xQlNVz8Og8kvArMtNROxVQuCaSnIDdD5 LKyWbRd2n9WGe2R8PzgCmr3EgVLrjyBxWezF0jLHwVN8 efS3rCj/EWgvIWgb9tarpVUDK/b58Da+sqqls3eNbuv7 pr+eoZG+SrDK6nWeL3c6H5Apxz7LjVc1uTIdsIXxuOLY A4/ilBmSVIzuDWfdRUfhHdY6+cn8HFRm+2hM8AnXGXws 9555KrUB5qihylGa8subX2Nn6UwNR1AkUTV74bU= ) ; KSK; alg = RSASHA256 ; key id = 20326 . 77796 IN DNSKEY 257 3 8 ( AwEAAa96jeuknZlaeSrvyAJj6ZHv28hhOKkx3rLGXVaC 6rXTsDc449/cidltpkyGwCJNnOAlFNKF2jBosZBU5eeH spaQWOmOElZsjICMQMC3aeHbGiShvZsx4wMYSjH8e7Vr hbu6irwCzVBApESjbUdpWWmEnhathWu1jo+siFUiRAAx m9qyJNg/wOZqqzL/dL/q8PkcRU5oUKEpUge71M3ej2/7 CPqpdVwuMoTvoB+ZOT4YeGyxMvHmbrxlFzGOHOijtzN+ u1TQNatX2XBuzZNQ1K+s2CXkPIZo7s6JgZyvaBevYtxP vYLw4z9mR7K2vaF18UYH9Z9GNUUeayffKC73PYc= ) ; KSK; alg = RSASHA256 ; key id = 38696 . 77796 IN DNSKEY 256 3 8 ( AwEAAeuS7hMRZ7muj1c/ew2DoavxkBw3jUG5R79pKVDI 39fxvlD1HfJYGJERnXuV4SrQfUPzWw/lt5Axb0EqXL/s Q2ZyntVmwQwoSXi2l9smlIKh2UrkTmmozRCPe7GS4fZT E4Ew7AV4YprTLgVmxiGP4unRuXkYOgQJXCIBpVCmEdUl i6X2sm0i5ZilU/Q+rX3RDw+eYPP7K0cJnJ+ZnvQDy14+ BFtreWl9enNQljgGpBp26lEp1z7AbvUfzkQNVCVGaM8j EaCSALXiROlwCQMOdj+tpLXFf99kdJnTQw2cpEr1uGs/ yENAJpoGhbjZAoIkXzDUBSlfFeYz7FWzH6gIe7M= ) ; ZSK; alg = RSASHA256 ; key id = 61809 ;; Query time: 1 msec ;; SERVER: 127.0.0.1#53(127.0.0.1) (UDP) ;; WHEN: Mon Nov 03 13:57:31 CET 2025 ;; MSG SIZE rcvd: 853

- Blog-Post: The 2024-2026 Root Zone KSK Rollover: Initial Observations and Early Trends

- ICANN KSK Rollover Files https://www.iana.org/dnssec/files

- RFC 9718 - DNSSEC Trust Anchor Publication for the Root Zone

| Event | Date | Description |

| Publication | 11 January 2025 | The successor key was introduced in the DNS root zone. |

| - | 10 February 2025 | The successor key should begin to be trusted by resolvers that follow the mechanisms described in RFC5011. |

| Rollover | 11 October 2026 | The successor key is scheduled to sign the zone; the current key will not sign the zone. Validating resolvers must have updated trust anchors to continue validating the root zone. |

17 DNSSEC Key-Rollover Automation

- A DNSSEC key rollover is a delicate process that needs to be done carefully

- Automation can prevent human errors in the process

- With BIND 9, a ZSK rollover can be fully automated

- A KSK rollover can be fully automated with a parent domain that supports Automating DNSSEC Delegation Trust Maintenance (RFC 7344/8078)

17.1 Automating DNSSEC Delegation Trust Maintenance (RFC 7344/8078)

- RFC 7344/8087 defines an automatic way to update the chain of trust towards the parent zone in an KSK key rollover

- The operator of the zone creates a new KSK for the zone and then publishes the new DS record or/and DNSKEY record for the parent zone in a CDS and/or CDNSKEY record in the zone

- The authoritative DNS server for the parent zone periodically polls the child zones for new CDS or CDNSKEY records

- Once a new CDS record is found, it will be validated against the

current KSK and DS records, and if it is valid, it will be imported

into the parent zone (replacing the DS record)

- If a new CDNSKEY record is found in the child zone, the authoritative DNS server of the parent zone will validate the record, calculate the hash to get a DS record, and will then replace the DS record with the newly calculated DS record

- BIND 9 supports CDS and CDNSKEY since version 9.11

- The

dnssec-cdsutility can change DS records for a child zone based on CDS/CDNSKEY records - CDS and CDNSKEY is already supported by some TLDs (Czech Republic

.cz, Switzerland.ch, Lichtenstein.li, Sweden.se…)

17.1.1 Bootstrapping DNSSEC with CDS/CDNSKEY

- The CDS/CDNSKEY records can be used to bootstrap a DNSSEC signed zone

- The operator of a DNS zone signs the zone and places the CDS/CDNSKEYs in the zone

- The parent domain operator polls all non-DNSSEC zones for the existence of CDS/CDNSKEYs. Is the same CDS/CDNSKEY record found for a specific time in the zone, the parent imports the records and creates the DS record in the parent zone, closing the DNSSEC chain of trust

- The exact requirements and rules for DNSSEC bootstrapping depend

on the registries policy. See for example for the

.ch(Swiss) and.li(Lichtenstein) Top-Level-Domains: https://www.nic.ch/security/cds/

17.1.2 Bootstrapping DNSSEC trust (RFC 9615)

- The challenge with bootstrapping DNSSEC: there is no established cryptographic trust between the zone and the parent zone DNS server

- This draft make use of already secured domains that hold the

host-names of the authoritative DNS servers for the zone to be

DNSSEC secured

- It only works for zones that have at least one NS record hostname outside the delegated zone (out-of-bailick), which is good practice for resilience

- In addition to the zone itself, the new CDS/CDNSKEY records are published as signaling-records in the domains of the zones nameserver hostnames

- Example:

- Zone to be signed

dnssec.workshas the following NS record setdnssec.works. 3600 IN NS ns01.dane.onl. dnssec.works. 3600 IN NS ns02.dnslab.org. dnssec.works. 3600 IN NS ns03.dnssec.works.

- The server

ns01andns02are located outside the zone, the serverns03is located inside the zonednssec.works - The zone

dane.onlwill publish the following signalling record (the CDS or CDNSKEY record):_dsboot.dnssec.works._signal.ns01.dane.onl. IN CDS ....

- The zone

dnslab.orgwill publish the following signalling record (the CDS or CDNSKEY record):_dsboot.dnssec.works._signal.ns02.dnslab.org. IN CDS ....

- Zone to be signed

- Because both the zones

dane.onl.anddnslab.org.are DNSSEC signed and provide the hostnames required for the delegation on the zone, the parent zone operator can now fetch the CDS or CDNSKEY in a DNSSEC secured way - When using secure DNSSEC bootstrapping, there is no delay in publishing the new DS record in the parent compared with the insecure "Accept after delay" procedure documented in RFC 8078.

- RFC 9615 "DNSSEC bootstrapping" has all the details.

- This RFC is already supported by the

.chand.liTLDs

17.1.3 Further Reading

- DNSSEC provisioning automation with CDS/CDNSKEY in the real world https://jpmens.net/2021/10/05/dnssec-cds-cdnskey-in-the-real-world/

17.2 RFC 9859 - Generalized DNS Notifications

- With automated DNSSEC delegation trust maintenance (RFC 8078), the

parent domain operator (most often the TLD operator) will "scan"

all child domains for new CDS/CDNSKEYs

- This is resource intensive

- It is done is intervals, for example 24 hours - changes to the CDS/CDNSKEY will propagate based on that interval - child zone operators need to wait multiple hours for the change to appear in the parent zone

- RFC 9859 - Generalized DNS Notifications (September 2025) extends the use of DNS notification (used for ages in DNS to inform secondary server of a new zone version to trigger a zone transfer) for other purposes

- One is to send a notify from the primary server of a child zone to

the primary server of the parent zone to inform the parent zone of

a new CDS/CDNSKEY

- No need for the parent to scan all child domains

- Faster propagation times (seconds instead of hours)

- Support for "Gerneralized DNS Notifications" is planned for BIND 9.22 (Q2/2026)

18 BIND 9 repositories for up-to-date BIND 9 versions

19 DNSSEC Best-Practices

19.1 DNSSEC br0k3n?

19.2 SHA1 phase out in Red Hat EL 9

19.3 Avoid SHA1

- The hash algorithm SHA1 is weak

- It should be phased out for existing DNSSEC zones

- It should not be used for new DNSSEC deployments (use RSASHA256 or ECDSA)

- Double-Signing zones with SHA1 and other (stronger) algorithms does not help as downgrade attacks are possible

19.4 Avoid UDP fragmentation

- UDP fragmentation can be used to attack DNS traffic

- There is a specific danger for DNS resolver that does not validate

DNSSEC

- But receive DNSSEC signed data, as DNSSEC signatures create large(r) DNS responses

- BSI Study: IP Fragmentation and Measures against DNS Cache Poisoning (Frag-DNS)

19.5 Avoid UDP fragmentation - DNS authoritative Server operators

- Avoid old(er) Linux kernels that are vulnerable to MTU downgrade attacks through ICMP spoofing (Long-Term/Enterprise Kernel)

- Configure the authoritative DNS server with an maximum UDP answer size of 1232byte (EDNS0 Buffer Size)

- Make sure the authoritative DNS server does respond on TCP port 53 (See RFC 7766 - DNS Transport over TCP - Implementation Requirements)

- DNSSEC sign your zones so that resolvers can validate

19.6 Avoid UDP fragmentation - DNS Resolver operators

- Enable DNSSEC validation

- Configure the authoritative DNS server with an maximum UDP answer size of 1232byte (EDNS0 Buffer Size)

- Make sure the DNS resolver can query DNS content over TCP

- Block fragmented DNS responses coming from the Internet in the Firewall (they should never occur with an EDNS0 buffer of 1232byte)

- RFC 9715 - IP Fragmentation Avoidance in DNS over UDP

20 DNSSEC troubleshooting

20.1 Checking DNS resolution issues

20.1.1 dig

The DNS name resolution tool dig can be used to test the general

function of a DNS resolver, or to test if an error condition exist at

the remote DNS authoritative servers of a domain.

- Testing one DNS resolver over UDP

To test the general connectivity and operation of a DNS resolver, a query for well known DNS data can be sent, such as for the list of name-server (NS records) of the root zone

".". The answer should contain the list of all 13 root name server in the Internet (with the namesa-m.root-servers.net)$ dig @IP-of-DNS-resolver NS .

- What are reasons we recommend using the IP address of a resolver instead of its name?

- Testing one DNS resolver over TCP

The DNS resolvers must also be reachable over TCP. To send a query via TCP, add the

+tcpflag to queries.$ dig @IP-of-DNS-resolver NS . +tcp

- You can save 33% typing by using

+vcinstead of+tcp. What doesvcdo? Check the manual page fordig(1).

- You can save 33% typing by using

- Testing reachability of all authoritative DNS servers

The

digfunction+nssearchwill first query all NS records for a given domain and then will try to query directly (without going to a DNS-resolver) the authoritative DNS servers of that domain:$ dig @IP-of-DNS-resolver example.com +nssearch

The function will print out the SOA record of the zone (here

example.com) for each DNS server that has send an answer to the query, including the SOA serial, the IPv4 and/or IPv6 address and the round-trip-time (RTT) of the query.All SOA serial numbers should show the same number, else there might be an issue with zone synchronization via zone transfer which might be a possible cause for DNS lookup problems.

- Which type of DNS servers (authoritative, recursive, primary, secondary) are at fault if the SOA serial numbers of a zone are not in sync? Who can correct the fault?

- Testing the resolution chain

The function

+traceindigwill trace the DNS name resolution starting from the root DNS server system down to the requested name.$ dig @IP-of-DNS-resolver example.com +trace

Only the very first query to find the root-server addresses will be done towards the DNS resolver given in the command, all other queries will be sent directly to the authoritative DNS servers. This function tests and prints one of usually many possible DNS resolution paths. A successful return of the command does not indicate that the resolution path is without errors, it is only an indication that at least one successful path exists.

- Testing for DNSSEC validation issues

If a DNS query returns a

SERVFAILanswer, it can be a DNSSEC validation issue at the DNS resolver, or it can be some kind of server malfunction on the DNS resolver or the remote authoritative server.In order the check for DNSSEC validation issues, the administrator can send a DNS query with the

+cdflag (Checking Disabled). With this flag set, the DNS resolver will skip DNSSEC validation and will return the DNS data todigeven in case the DNSSEC validation would fail.So if a DNS query returns data when

+cdis set, but returnsSERVFAILwhen+cdis not set, this indicates a DNSSEC validation issue. If the answer is alwaysSERVFAIL, it is some other kind of problem (usually not DNSSEC).

20.1.2 External web services to check DNS

Several website services exist that help DNS administrators to check the health of a DNS system

- Zonemaster

The website Zonemaster https://zonemaster.net is a collaboration between the French TLD registry AFNIC and the Swedish registry IIS. The website takes a domain name and will generate a report of errors and best practice recommendations of the setup of this domain name.

- DNSViz

DNSViz https://dnsviz.net is a tool for visualizing the status of a DNS zone. It provides a visual analysis of the DNSSEC authentication chain for a domain name and its resolution path in the DNS namespace, and it lists configuration errors detected by the tool.

20.2 Looking into DNSSEC validation issues

DNSEC validation issues are often a problem with misconfiguration at the authoritative DNS server side of the domain, not an issue of the DNS resolver system. However to be able to debug DNSSEC issues, for example to decide if an NTA (negative trust anchor) should be inserted into the DNS resolver system to temporarily disable DNSSEC validation for a specific domain, the DNSSEC validation issue should be investigated first.

20.2.1 DNSSEC validation troubleshooting with "delv"

The tool delv is part of the BIND 9 DNS server and implements a full

DNS resolver and DNSSEC validator inside the command line tool. This

tool works very similarly to dig (and shares the same command line

syntax), but where dig always needs a DNS resolver to get the DNS

information, delv can query the data and can validate the DNSSEC

information itself.

20.2.2 Message trace

The flag +mtrace enables the message tracing in delv, the tool

will print all DNS queries and answers during the processing of the

query.

$ delv example.com +mtrace

20.2.3 Validation trace

The flag +vtrace will print a debug trace of all DNSSEC validation

steps the tool will do in order to validate the received DNS answers

$ delv example.com +vtrace

20.3 Exercise: DNSSEC troubleshooting

- A customer owns the domain

dnssec.works. This domain has 5 sub-domains,fail01.dnssec.workstofail05.dnssec.works- all 5 subdomains contain DNS errors on the IPv4 address record(!)

- Your task: find out the DNSSEC issues with these zones

- Use

digto find the issues - Also use the websites https://dnsviz.net and https://zonemaster.net to confirm your findings

21 Dealing with DNSSEC resolver issues

21.1 Negative Trust Anchor

- Often DNSSEC validation issues are caused by operational issues

(expired DNSSEC signatures, DS record and DNSKEY KSK mismatch etc)

- Negative Trust Anchors can be used to disable DNSSEC validation for mis-configured domains

- Negative Trust Anchors are defined in RFC 7646 Definition and Use of DNSSEC Negative Trust Anchors

- Negative trust anchors (nta) disable DNSSEC validation for a

specific domain for a certain amount of time

- NTA can be used by operators in case a misconfiguration for a remote DNSSEC signed zone is detected. Care should be take to check that the DNSSEC validation failure is indeed a misconfiguration and not attack

- Domains with an NTA are processed as if there is no trust-anchor for that domain

- NTAs are stored and are persistent across BIND 9 restarts

- BIND 9 checks the domain periodically. Once the domain starts validating again, the NTA for the domain is removed

- NTAs have a lifetime (maximum one week) and expire automatically

- Example: adding an NTA (for 60 seconds):

% rndc nta -l 60 fail01.dnssec.works Negative trust anchor added: fail01.dnssec.works/_default, expires 18-Aug-2016 13:52:19.000 % rndc nta -dump fail01.dnssec.works: expired 18-Aug-2016 13:52:19.000 % ls -l /var/named/_default.nta -rw-r--r--. 1 root root 44 Aug 18 13:51 /var/named/_default.nta % cat /var/named/_default.nta fail01.dnssec.works. regular 20160818115219

- Example: removing an NTA

% rndc nta -l 86400 fail02.dnssec.works # add a NTA for 1 day Negative trust anchor added: fail02.dnssec.works/_default, expires 19-Aug-2016 13:56:22.000 % rndc nta -dump fail02.dnssec.works: expiry 19-Aug-2016 13:56:22.000 % rndc nta -r fail02.dnssec.works # remove the NTA Negative trust anchor removed: fail02.dnssec.works/_default % rndc nta -dump # NTA is now gone

21.2 Exercise: negative trust anchor for failNN.dnssec.works

- In the chapter on DNSSEC troubleshooting we've learned about the

broken DNS zones

fail01.dnssec.workstofail05.dnssec.works - Create negative trust anchor (NTA) for

fail01tofail03in your DNSSEC validating resolver machinednsrNN - Check that a client can now retrieve DNS data from these zones

$ dig @127.0.0.1 fail01.dnssec.works A

- Remove the NTA for

fail01.dnssec.works. Check that the zone now does not validate and returnSERVFAIL

21.3 Recommendations for DNS resolver operators

- Make sure your DNSSEC validating resolver supports DNSSEC negative trust anchor

- Test the negative trust anchor function

- Document how to add a negative trust anchor

- If your software does not support automatic removal of NTAs, implement an automation (connected to your DNS resolver monitoring)

- Do not implement automatic NTA additions, activating an NTA should only occur after human inspection of the DNSSEC validation problem

- Read the Internet Draft Recommendations for DNSSEC Resolvers Operators

21.4 DNSSEC Resolver and time

- DNSSEC validation is time sensitive

- The DNSSEC signatures have expire and inception (become valid) times that the DNS resolver must check

- Without a correct time on the DNSSEC resolver machine, DNSSEC validation might fail

- Recommendation: Implement automatic time synchronization for the DNSSEC resolver (NTP, PTP)

- Make sure the time synchronization has no dependency on (DNSSEC)

DNS name resolution (no circular dependecy or

chicken-and-egg-problem)

- A great usecase for Precision Time Protocol (PTP https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Precision_Time_Protocol) if available in the network

22 DNSSEC Risks

22.1 Risk: operating a DNSSEC validating resolver

- A DNSSEC validating resolver will respond with the DNS error

SERVFAILto the DNS client whenever it detects a mismatch in the DNSSEC chain of trust or a bogus or expired DNSSEC signatureSERVFAILis not DNSSEC specific, there are many error situations that can result in anSERVFAILresponse- The end user cannot detect that the DNS name resolution fails because of DNSSEC security and will blame the operator of the DNS resolver for the outage

22.1.1 Solutions to mitigate this issue

- Open communication with the end user about DNSSEC issues

- Active monitoring for DNSSEC validation issues on the DNS resolver